This essay was originally part of a series of documents that were shared with my former department chair at the University of Texas at San Antonio over several years. Later, I shared some of this information with the new incoming President in a letter I wrote him in December, 2017. After it was clear that the university would do nothing to fix these issues, I complied these essays and data, as well as other data and essays, and I submitted it to university officials in the fall of 2018. Then I quit teaching in Texas.

“On paper, her school claimed that almost all of its graduates were headed for college. In fact, the principal said, most of them ‘couldn’t spell college, let alone attend.’”

Introduction: Cheating Cultures in Educational Institutions

UTSA has a serious problem that urgently needs to be acknowledged and addressed by administrators, faculty, and student affairs staff. Most freshman entering UTSA are not prepared for academic success in college, which is why UTSA has traditionally had low retention and graduation rates. In order to support that claim, I will be providing an interdisciplinary synthesis of many bodies of academic literature in conjunction with original observations and research. Rather than dealing with this serious problem, some faculty at UTSA are engaging in various forms of malpractice and fraud, especially in the Writing Program, which will be the focus of this report.

Why are students unprepared for success in college? There are many reasons for this predicament, including inadequate Texas funding of K-12 schools, especially during the Great Recession of 2008 and its aftermath when hundreds of millions of dollars were cut from Texas schools, thousands of teachers were laid off, class sizes were increased, and the curriculum was cut. Other reasons include inequitable educational resources in Texas K-12 schools, and low student motivation to succeed academically, which is tied both to student’s psychology and their parent’s socio-economic status.

In Texas, as in most states around the U.S., students are graduating high school not only unprepared for college, but also without basic literacy and numeracy skills, including the ability to read and write. Worst of all, many Texas high schools are fraudulently awarding diplomas to students who should not be graduating because these students lack basic numeracy, reading, and writing skills. Nichols and Berliner (2007) analyzed a 2003 study, which researched 108 schools in Texas. In half of these schools, “70 percent or more students were considered at risk of academic failure,” and yet these schools graduated nearly all of their students and claimed a dropout rate of only “1 percent or less” (p. 83). In 2000-2001, Houston, Texas boasted a 1.5 percent drop out rate, yet one Houston principal admitted to a researcher, “On paper, her school claimed that almost all of its graduates were headed for college. In fact, the principal said, most of them ‘couldn’t spell college, let alone attend’” (qtd. in Nichols & Berliner, 2007, p. 83). Texas is not alone. This kind of educational fraud is happening all over the U.S., most famously in Atlanta, where 35 educators where charged, and 11 were convicted, on state racketeering charges (Mitchell, 2017).

Just a couple of months ago, a teacher in Bastrop, Texas published a resignation letter that went vial around the country (Mulder, 2018). She discussed the demoralizing environment in her school where she doesn’t have the materials that she needs to teach due to budget cuts, so she spends her own money to invest in supplies, only to have her students damage or destroy them. She also explained that she would be failing almost half of her class because they don’t have the necessary skills, and because they won’t complete assignments. She explains that Bastrop administrators are doing nothing to address this situation, they side with non-performing students and their parents, and they blame teachers for students’ problems, all of which makes the situation worse. She exclaimed, “My administrator will demand an explanation of why I let so many fail without giving them support, even though I’ve done practically everything short of doing the work for them” (para. 7).

These low motivated and academically unprepared students not only manage to graduate from Texas high schools, but then they end up enrolling in community colleges and non-selective state universities, like UTSA. There is enormous social pressure for everyone to go to college, but most unprepared high school students will drop out of college without ever earning a degree (Rosenbaum, 2001), and many of these dropouts will have unprecedented levels of student loan debt (Golderick-Rab, 2016). At open-door community colleges across the U.S. the dropout rate exceeds 70 percent (Beach, 2011). Since its inception, UTSA has been a non-selective university and it admits many unprepared students. Thus, it has always had low retention rates and low graduation rates, with currently less than 40% of freshman graduating with a degree in six years, which is the highest graduation rate that UTSA has ever had.

I have taught first-year freshmen in the Writing Program at UTSA for the past eight years. I have found that most of my students do not have the basic student skills, let alone the prerequisite reading, writing, and thinking skills required to successfully pass Writing classes, let alone earn a college degree. I will be documenting the academic metrics of my students later in this report. Worst of all, many of these students who lack basic skills have already passed through writing classes at UTSA where they learned almost nothing, even though the majority of them received A and B course grades.

K-12 schools in Texas are failing to prepare all students for success in college, which is the root of the problem that I am addressing, but institutions of higher education in Texas are exacerbating this problem by not properly screening students, by not keeping academic standards high, and by not providing the necessary support that high-risk students need. In particular, UTSA has inadequate enrollment procedures to ensure that incoming students are emotionally and academically prepared for success in college. This includes the psychological readiness of students, as I have seen that about 1-2 percent of my students suffer from serious mental health problems, which prevent them from being successful students. UTSA also has faculty inadequately trained to teach, especially adjunct faculty teaching freshmen. And most importantly, rather than understand the problems of unprepared students and do the hard work of educating them, many faculty at UTSA are lowering academic standards and passing these unprepared students with inflated grades.

Lowering academic standards harms unprepared students in several ways. First, students are allowed to pass without demonstrating real knowledge, which gives them an inflated sense of accomplishment, which will hinder future attempts at learning when they encounter more responsible faculty with higher academic standards. A lack of learning will also eventually catch up with these students. They are at high risk of failing more difficult classes as they move into their junior and senior year, and this will increase their chances of dropping out. Worst of all, because they were socially promoted, these students spent thousands of dollars and accumulated higher amounts of debt without learning any real knowledge or skills, and so they will drop out of college worse off than when they started.

Plus, pandering to unprepared students with lower academic standards also harms high achieving students who will not get the full education they want, which will limit their opportunities to be successful in graduate school or the labor market. This situation also harms committed scholar-teachers who have high academic standards and use evidence-based teaching practices because students complain about the hard work and double standards of more competent faculty, and administrators complain about higher D/W/F grades.

I have spent the last eight years at UTSA wresting with this situation by spending thousands of unpaid hours pouring through the academic literature and tirelessly innovating in my classrooms, including developing my own curricular materials tailored to my students’ needs. As the philosopher Richard McKeon (1953/1990) pointed over a half century ago, teaching and scholarship should be deeply intertwined (p. 34). I have always used my passion and commitment as a scholar to better inform my teaching and the development of my curriculum. I have used my academic skills to study not only the subjects of literacy, epistemology, and communication, which I teach, but also the predicaments of my students at UTSA and the Writing Program that is supposed to be training them. For the past eight years, I have been formally assessing and documenting student motivation and academic proficiency. I have also been studying the quality of the faculty and the curriculum of the Writing Program, as well as some of the institutional policies of UTSA. I have tried to understand the complex causes of student failure so that I could develop innovative ways of increasing student motivation and achievement, and I have also tried to share this knowledge with my colleagues to promote department and institutional reform.

While I am focusing on the Writing Department at UTSA, I want to reiterate that many schools around the country have endorsed “playing school” and/or adopting a “cheating culture” to not only deal with unprepared students who cannot or will not learn, but also to deal with unrealistic policy directives that have been pushed by politicians and school administrators (Nichols & Berliner, 2007, p. 33). I will explain how UTSA is one of those schools, but it is not alone in its predicament. I have talked to a colleague at UT El Paso, which is facing the same problems as UTSA, and I have personally seen these same problems at Austin Community College and St. Edwards University, where I have also worked as an instructor. As educational scholars Nichols and Berliner (2007) have documented, “through the overvaluing of certain indicators, pressure is increased on everyone in education. Eventually, those pressures tend to corrupt the educational system” (p. 34). Because of the widespread political pressure to increase student success metrics, especially retention and graduation rates, there is widespread “potential” at all levels of our educational system “for manipulating data” (p. 84) and engaging in various forms of educational malpractice and fraud to cook the books.

Around the country, educators feel enormous pressure to play school, pass underperforming students through the system, and award the maximum amount of credentials. This pressure is corrupting not only K-12 schools, but also institutions of higher education. In 2006 the Spellings Commission released its final report, A Test of Leadership: Charting the Future of U.S. Higher Education. In this report the committee noted, “There are disturbing signs that many students who do earn degrees have not actually mastered the reading, writing, and thinking skills we expect of college graduates. Over the past decade, literacy among college graduates has actually declined. Unacceptable numbers of college graduates enter the workforce without the skills employers say they need in an economy where, as the truism holds correctly, knowledge matters more than ever” (p. vii).

Like the cheating teachers in the Atlanta scandal, my colleagues in the Writing Program at UTSA are not bad people with sinister motives. I believe that most of them sincerely want to help students succeed in college and in life, and most of them feel pressured by our Department Chair and the administration. Yet despite their good intentions, as documented in studies around the country at all levels of schooling, unprofessional and fraudulent practices, including rampant grade inflation, end up hurting students in many ways, especially the most disadvantaged (Marcus, 2017). The unprofessional and fraudulent practices in the Writing Program must stop, for the benefit not only of faculty and students, but also to protect UTSA’s academic integrity so that our university can rise to Tier I status, and thereby use its future position to better the people of San Antonio and the entire state of Texas.

I believe in transparency, the importance of data and scientific analysis, and the power of knowledge to transform policy and practice. I want to publicize the problems that UTSA faces so that these problems can be acknowledged and addressed with new policies and better practices. I sincerely want to see UTSA develop into a Tier I university that can make a real impact in the lives of students, especially disadvantaged students who will benefit the most from a college education.

Malpractice and Fraud Due to Mismanagement in the Writing Program at UTSA

I have been a faculty member in the Writing Program at UTSA since 2010. From the beginning, I noticed that this department was dysfunctional and beset by many problems. I have formally studied higher education and published on the subject, so once I arrived, I immediately started collecting and analyzing data on student motivation and academic achievement, as well as the strengths and flaws of the Writing Program curriculum, program faculty, and UTSA policies. Over the past eight years, I have shared my data and preliminary conclusions with my colleagues many times, but I came to realize that most of my colleagues did not want to address the problems our department faced. Instead of researching and engaging with these problems, the Chair of the Writing Program has not only ignored the problems I addressed, but she has continued or initiated many counter-productive and unprofessional practices. I also think that some of these practices constitute forms of educational fraud.

In her defense, the Chair has told me that both our current Dean and our previous Dean have supported her unprofessional and fraudulent policies. So while I am laying responsibility primarily on the Chair in this report, other senior administrators at UTSA, and the institutional culture they have fostered, have most likely contributed to the dysfunctional nature of the Writing Program.

First of all, it is important to understand that most faculty in the Writing Program have only a two-year master’s degree in English, most of which were earned low-tier public universities, like UTSA. Further, some of our faculty are graduate students in the English department who are unprepared and unqualified to teach. Only a few of our faculty have delivered conference papers, and just two or three have published an academic paper. Most of our faculty don’t even read academic research of any kind, let alone write and publish research. Many of our faculty watch tv, play video games, read novels, or use social media during their office hours, rather than engage in serious scholarship, like research, writing academic papers, conducting peer-review, or engaging with public policy.

Maybe one or two members of our department, beside myself, actively engage in academic research or publish scholarship. And as far as I know, I am the only person who is an active peer reviewer for academic journals or professional scholarly associations. I am the only person serving on the editorial board of an academic journal. I am the only person in the department to have written and published academic books, which have been peer reviewed and widely cited by other scholars around the world. I am also the only faculty member in the department whose scholarship has been formally endorsed by a President of the MLA, the formal professional body that governs the discipline of English.

Most of my colleagues have only two years of graduate school, studying fictional literature, a subject that is completely unrelated to the current curriculum of the Writing Program at UTSA, which is focused on academic writing, critical thinking (including quantitative reasoning), and argumentation. Almost none my colleagues have any formal training in quantitative reasoning, and many are hostile to the very subject of math. Further, most of my colleagues have never professionally written anything, which is deeply troubling to say about a Writing Program at a research university aspiring to teach Tier I status. Unlike many other traditional academic subjects, which are abstract and theoretical, writing is a practice and a craft, and you can only teach it well if you actually practice it as a professional, especially I would argue, if you are teaching academic or scientific writing, which includes the important process of critical peer review.

Low-quality faculty is one of the core problems our department faces, but no one in the Writing Program wants to discuss this problem, especially the Chair. I would argue that this topic is taboo largely because of the widely documented “Dunning-Kruger Effect” (Nichols, 2017, pp. 43-44). The more ignorant and incompetent people are, the less likely they can see their ignorance and incompetence; thus, the more likely they believe they are competent, and the more likely they will resist new information to fix the problem they cannot see or acknowledge. Low-quality faculty simply cannot see, let alone understand, their many inadequacies.

Why does the Writing Program have so many low-quality faculty? Largely it’s due to institutional policies at UTSA. For adjuncts, UTSA offers low pay and poor working conditions teaching unprepared undergraduates, so it does not attract highly qualified faculty, especially for programs that focus on freshmen (the tenure track is a different story, and I am not addressing tenure track faculty in this report). I have heard that many other departments at UTSA suffer from similar problems as the Writing Program, and many of my colleagues have claimed that the new Academic Inquiry program is the most dysfunctional program at UTSA, but I have no direct knowledge or data to address that claim.

When I was hired at UTSA, my education, experience, and scholarship were ignored, and I was placed at the bottom of the pay scale at the poverty-level wage of $24,000 a year, plus benefits (before taxes). To add insult to injury, this was the full-time salary, and as a new adjunct, I was only given full-time status fall semester and then part-time status spring, so I was making only $18,000 a year (before taxes and mandatory retirement contributions), with paid benefits for only four months because I could not afford the pay the premiums for the rest of the year. This was much less then I was paid for the same position in California or Oregon. Few competent scholars would put up with such dismal compensation. Like almost all of my adjunct colleagues, I have had to work a second or third job to survive financially.

While these poor working conditions are a problem for all UTSA adjunct faculty, there is another problem unique to the Writing Program because it mostly employs faculty with English degrees. As I will point out in the next chapter, due to the arbitrary history of English as an academic discipline, most of my colleagues have not been trained in the subjects they have been hired to teach. With Masters degree in English, most of our faculty have no formal training in the core fields of rhetoric, composition, communication, or critical thinking (let alone quantitative reasoning) that govern our curriculum. Further, I don’t think any faculty in the department, other than myself, has training in the field of education, which covers teaching, student learning, curriculum, and educational assessment. Given the challenging student population we are trying to teach, knowledge of education is a must if our program seeks to be successful.

A poorly trained adjunct faculty would not necessarily be an insurmountable problem if they were properly supervised and trained with ongoing professional development. However, there has been no proper supervision or real professional development in the Writing Program. Traditionally, university faculty engage in faculty development via attending academic conferences and engaging in scholarship. But adjuncts at UTSA are so impoverished that few of them can afford to attend a conference. With only a Master’s degree, most are not adequately trained to engage in scholarship or research, and for those that do have the necessary training and aspire to publish, they are often too busy to do so because they have to work multiple jobs to survive.

But the Chair has also actively subverted basic university standards of faculty professionalism, largely because she had shirked her responsibility to adequately supervise or train low-skilled adjuncts. She has disregarded the essential practice of “professional development” that is mandatory in all top-tier research universities. Instead of engaging with the academic and scientific research that governs our multi-disciplinary curriculum, she uses bi-yearly meetings to do two things. First, she takes hours to restate all of the basic policies published in the Faculty Handbook and discuss institutional and departmental news, which is a useless and demeaning ritual – all of this information could easily be sent to faculty via email. Then she has untrained faculty members hastily put together half-baked presentations (rarely addressing even a single academic source) on topics they are usually unqualified to discuss. Or she has unqualified textbook representatives give the department a presentation on how to teach to the textbook. These practices do not constitute “professional” development.

I can remember only three times in eight years that we have had a trained scholar speak during our professional development days, and I was one of those three speakers. I agree with Brint (2008) and Grubb (1999) that higher education faculty need greater professionalization when it comes to teaching and being responsible for student learning, especially adjunct faculty (hence one of the reasons why I wrote this report). Brint (2008) has called for the “reconstruction of college teaching as a profession” (p. 5). I have continually urged the Chair and the main coordinating committee to offer real professional development engaging our faculty with the academic and scientific literature, but no one wants to spend the time, money, or effort that real professional development would demand.

Our department “norming” sessions are another example of how university standards of faculty professionalism have been subverted. Once each semester, all faculty gather in small groups to evaluate three student essays from the previous year. These meetings could be an invaluable time to discuss research on the core concepts of our curriculum, and also how best to teach these concepts, as well as the subjects of student learning, curriculum, and educational assessment. But in most meetings there is no critical assessment of teaching or student learning, or any learned discussion of any topic. The Chair selects mostly inexperienced and unqualified faculty to lead these meetings. Most don’t know what they’re doing, so they just follow a prescribed and mindless ritual initiated by The Chair. Rather than discuss best practices in the scholarly literature, these “norming” sessions usually reinforce unprofessional subjective opinions and common sense. When listing to my colleagues evaluate student writing, it is clear that most of them suffer from what medical researcher Archie Cochrane calls “the God complex,” a common ailment of semi-professionals and non-professionals: They don’t need research or data to back up their claims; “they just know” the truth because their subjective intuition tells them its true (qtd. in Tetlock & Gardner, 2015, p. 31).

While the Writing Program does engage in a yearly assessment process, I found that this process is deeply flawed, if not possibly fraudulent. For one, if you read the actual assessment reports you will see that some of the numbers are inconsistent, which shows that these reports are not carefully put together. Further, the department does not have specific, measurable, and valid SLOs or core course topics, nor are there any calibrated assessment tools to measure any specific or objective evaluative criteria. In fact, The Chair has ignored my continued requests for clear Student Learning Objectives and core course topics so that faculty can better assess which students demonstrate the necessary skills needed to pass a class, especially in terms of the transition from Writing I to Writing II. I finally got these core concepts into the latest report of the main coordinating committee this year; however, in a recent email telling the department about these changes, it appears that they have been deleted, so I’m not sure if these core concepts have been made official policy, or if they have been put on hold or discarded.

In order to illustrate the Writing Program’s lack of valid SLOs, take for example the grading standards and learning objectives set forth in our Faculty Handbook for 2017-2018. Here are some of the vague standards for an A paper: “not commonplace or predictable,” “original,” “polished,” “strong,” “varied,” and “well-chosen” (p. 10). Or take some of the program goals for WRC 0203: “address the needs of different purposes” and “use appropriate format, structure, voice, tone, and levels of formality” (p. 49). I don’t know what these words are supposed to mean, and I certainly could not see them or objectively evaluate them in a student paper.

Philosopher Harry G. Frankfurt (2005) calls this sort of vague verbiage “bullshit,” which is language that cannot be clearly understood or empirically verified. Frankfurt (2005) argues that bullshit is worse than lying because people are “not even trying” to be accurate, and more importantly, because they are not “committed” to the truth of their statements (pp. 32, 36). Frankfurt (2005) criticizes bullshit as “empty, without substance or content…No more information is communicated than if the speaker had merely exhaled” (pp. 42-43). When the Writing Program officially uses and endorses vague, “bullshit” criteria like this, each faculty member will subjectively grade in idiosyncratic ways. Vague SLOs lead to invalid assessments of student work, and also to an unfair range of scores, not only between teachers, but also between assignments in the same class.

Another example of vague, “bullshit” SLOs can be found in Writing Program definitions of “critical thinking.” These official definitions are vapid, widely inconsistent, almost completely false, and unconnected from the academic disciplines of psychology and philosophy, which govern the concept and practice of critical thinking. For the portfolio assessment in the Faculty Handbook, the “critical thinking” objectives include: “summary, paraphrase, analysis, evaluation, and critique,” “thoughtful selection and meaningful synthesis of supporting evidence” (p. 74). None of these terms are directly connected to the actually definition of critical thinking. For the Core Curriculum Appendix I, critical thinking standards are: “creative thinking, innovation, inquiry, analysis, evaluation, and synthesis of information” (p. 45). Again, this list of vague and unconnected words is not connected to the definition of critical thinking. And for the program goals of WRC 0203, critical thinking supposedly means “use writing and reading as resources of inquiry and communication,” “recognize, understand, summarize, and evaluate the ideas of others,” “understand the power of language and knowledge,” and “understand the interactions among critical thinking, critical reading, and writing” (p. 49). As far as I can tell, whoever wrote this handbook was just mindlessly writing vague words or just making stuff up. None of these definitions of critical thinking is consistent, let alone coherent or accurate.

How can a program teach the core skill of critical thinking when nobody actually knows what it means, let alone how it is done or how to assess it? I made this exact point to the main departmental coordinating committee several times, and yet no one understood what I was saying. My colleagues think the meaning of critical thinking is obvious because it is simply a matter of common sense, and apparently they can’t see, or chose not to see, the inconsistent and incoherent lists of vague words in our Faculty Handbook. As a scholar who has published on epistemology and cognition, I’m embarrassed to be associated with the meaningless, confused, and false official language of our department on critical thinking, which was obviously written by amateurs who had no understanding of what they were talking about.

The vague and sometimes meaningless SLOs are just one part of an imprecise and invalid system of “holistic grading,” which the Chair has instituted, with the support of many colleagues. This subjective grading system leads to inflated grades that are not correlated with actual student knowledge or skills. This system is usually applied inconsistently, and the data collected is often invalid because the rubrics allow a wide range of subjective opinions. Writing Program faculty have no training in, or knowledge about, educational assessment, and so they don’t understand how and why their holistic rubrics and subjective evaluations are flawed. In fact, the Chair and many of my colleagues are biased against the very idea of collecting objective data and conducting educational assessments. No one in the department, except for myself, seems to understand the concept of validity or the value of assessing objective learning standards.

As I will demonstrate later in this report, I have uncovered limited student learning in the Writing Program. I believe that the lack of student learning is a direct result of the lack of objective SLOs and of invalid, holistic assessment instruments, which in conjunction with departmental and institutional pressure, lead to low and subjective academic standards and also to grade inflation, which can be seen as forms of academic fraud. Faculty subjectively judge student work, use low standards, and inflate grades that are unconnected with real student knowledge or skills, rather than do the harder work of validly assessing objective criteria.

While I am very concerned about grade inflation and lack of student learning in the Writing Program, I am more concerned with the fact that the Chair seems to be orchestrating this fraud, both directly through departmental policy, and indirectly through her comments and the norms she has set. She makes it clear to faculty that the majority of our students should pass our classes, regardless of actual effort or academic performance. She also makes it equally clear that she views failing grades as the fault of incompetent instructors, not the result of low student achievement or low motivation. Thus, most of my colleagues are not only using holistic and subjective rubrics to award inflated grades that are disconnected with actual student knowledge or skills, but they are also awarding lots of extra credit and empty points for attendance and participation in an effort to artificially boost student grades and maintain the Chair’s mandated grade distribution.

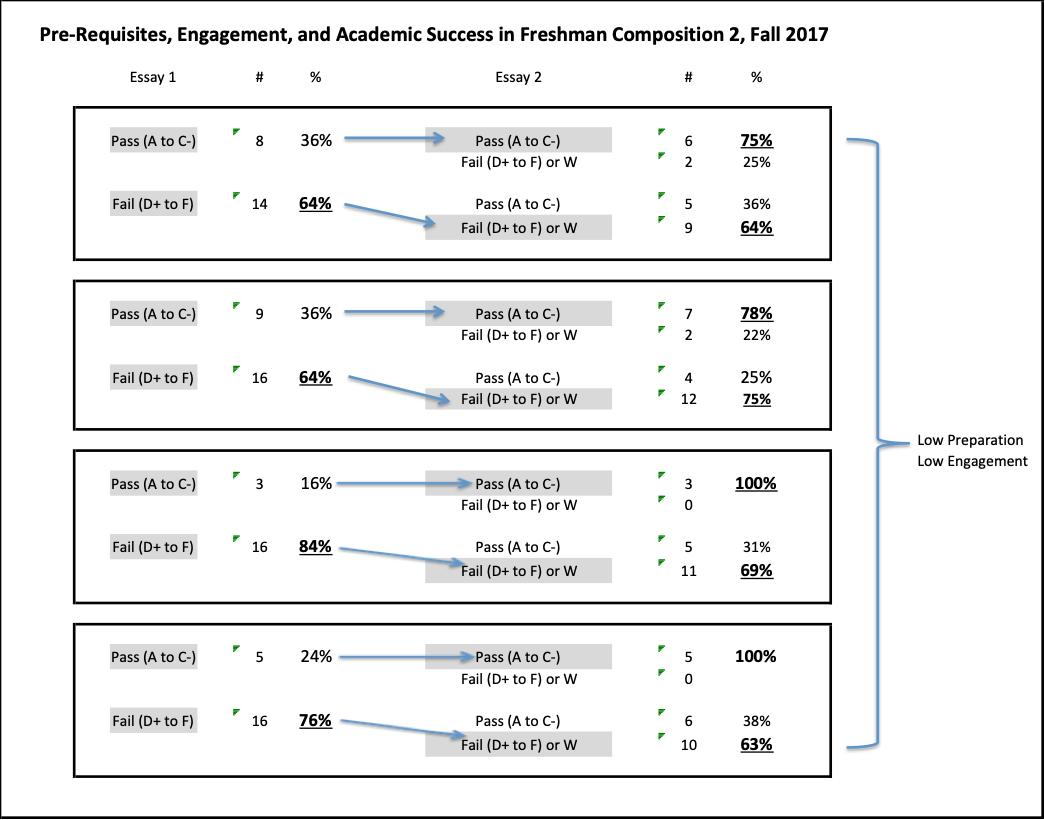

Suspiciously, our department has maintained the same basic departmental grade distribution every semester for many years. In the Writing Program, 80 percent of students consistently earn passing grades every semester, and over 60 percent consistently earn A or B grades. Interestingly, this inflated grade distribution has always been much higher than our yearly program assessments, which reveal a passing rate about 11 to 15.5 percent lower. On these yearly assessments, the Writing I average score went from 73 percent passing in 2015-2016 down to 70 percent passing the following year, while the Writing II average went from 75 percent in 2015-2016 down to 69 percent the next year and then down to 67.9 percent last year. The yearly assessments show a similar downtrend, albeit with a much softer slope, as I have found in my own classes, which can be seen in the previous chart (data on my students’ performance at the start of the semester is indicated on the lower dotted line “Essay 1 Pass”). While I think the yearly reports are a more accurate reflection of student skills than course grades, I still think these yearly assessments are inflated, due to untrained faculty, vague SLOs, and subjective holistic grading techniques.

The official numbers publicized by the Writing Program sound impressive, and that’s exactly what the Chair and the rest of my colleagues want UTSA administrators to think. However, my research shows that the majority of students in our department cannot read, write, or critically think, and I have hundreds of student essays to prove it. Worse, students are passing through Writing I at UTSA without mastering the basic prerequisite skills that are supposed to be taught in that class. As the chart above shows (the lower dotted line “Essay 1 Pass”), last spring only 22 percent of students in my Writing II class could demonstrate core Writing I skills, which was down from 43 percent in Spring 2016. I have consistently found that over half of the students who “pass” Writing I cannot demonstrate most core sills, including how to read. I will discuss this issue with more data later in this report. For now I want to point out, as the chart above illustrates, that my measurements of student competency have been steadily decreasing since 2016, yet the departmental grade average has held constant, which suggests that not only are my colleagues are artificially inflating grades to keep them in line with traditional standards, but they are consistently inflating grades in roughly the same proportion every semester, which suggests coordination, if not collusion.

The Chair prints the grade distribution of each faculty member every semester and she criticizes any faculty member whose distribution does not match departmental averages, which (as it states clearly in our Faculty Handbook) leads to lower performance ratings, which in turn leads to lower rates of promotion and less employment via less classes offered the following semester. I have been a victim of this vicious circle for years. The majority of my colleagues who consistently inflate their grades also consistently earn high scores on student evaluations, while my dropping grade distribution has matched my dropping student evaluation scores. It is interesting to note that these scores can vary a lot between different sections of the same class during the same semester, which clearly show that it is not the instructor’s teaching that is being measured but the subjective feelings and opinions of students. In effect, the Chair is coordinating department-wide fraud by demanding that faculty meet inflated grade distributions, which produce inflated student evaluation scores, and she punishes faculty that fall below her prescribed distribution levels. I tried to collect more precise data on this issue last year, but my colleagues verbally assaulted me for even talking about this issue, and the Chair told me that the Dean doesn’t see any problem with the Writing Program’s inflated grade distribution.

This fraud is further enabled by the Chair’s misuse of student comments and student evaluations, which constitute 30% of our yearly employee evaluations (as stated in the Faculty Handbook), although I suspect that student comments used to carry much more weight in the past. Faculty who lower standards and inflate grades get higher student evaluations and less complaints because students don’t have to work as hard to get high grades and most students pass a class regardless of effort or skill. In contrast, faculty with high academic standards award objective grades tied to the actual academic performance of students, which means students have to work harder to demonstrate real learning, and often receive lower grades in the process, which causes students to complain and give instructors lower evaluation scores – which, in turn, leads to lower performance ratings by the Chair, lower or no promotions, and reduced or loss of employment. It is a vicious circle. So it is easy to see why most faculty in the department participate in the fraud that the Chair is orchestrating.

Because my colleagues want steady employment with the least amount of student complaints, they lower their academic standards and they do not challenge students to demonstrate real learning. I have personally seen some colleagues give students meaningless and vapid instruction, whereby students simply have to unthinkingly follow a prescribed ritual to receive a passing grade. My colleagues are passing students (if not giving them As and Bs) who can’t read, write, or critically think. One of my students last semester confided in an essay, “My last writing course I had taken my first semester had been a breeze” (Student #1). Another student explained, “This course [my Writing II course] took me by surprise” because “in none of these schools [previously attended] was I introduced to the importance of objectivity over subjectivity and how to correctly identify points and thesis within works” (Student #2). Students are passing classes at UTSA with an inflated sense of knowledge and skill, which will result in future struggles when they eventually reach a class (or job) where they actually have to meet objective standards to succeed. I find this situation to be deeply troubling, and I consider it not only unethical, but also a violation of the academic integrity of UTSA and of the rights of our students as citizens and customers who deserve a real education for their tuition dollars.

While unprofessionally low standards and the fraudulent practice of enforced grade inflation are the most serious issues affecting our department, the Chair has also intentionally subverted some other important UTSA policies, which have lowered the quality of teaching and student learning in our department.

Ironically, our department has been tasked by UTSA to teach quantitative reasoning, which is not actually happening in most of our writing classes because English teachers are notoriously fearful of math. Instead of quantitative reasoning, many of my colleagues teach how to subjectively opine or lie with descriptive statistics. For the most part, the Chair appointed unqualified faculty members to lead the quantitative reasoning and writing initiative (the one qualified faculty member retired soon after the program was initiated). Most members of the department have no understanding of quantitative reasoning or descriptive statistics, and some members are actively hostile towards the practices data collection and scientific objectivity.

In the Writing Program Faculty Handbook (pp. 19-20), someone has badly summarized and pasted block quotes from the UTSA report on Quantitative Scholarship. I have not read the original documents, so I cannot judge its contents, but I can assess how it is being summarized and presented to our faculty. There is a bunch of empty language framing a vague purpose, like “understand and evaluate data, assess risks and benefits, and make informed decisions” (p. 20). What does this mean exactly and how is it done? Few in our department could hazard a guess.

Nowhere in the Handbook is there any definition of quantitative reasoning or how it is concretely done (for example a discussion of descriptive vs. inferential statistics, probability theory, the concept of validity, or sampling, including sample size and sample bias). Instead of concrete and knowledgeable directions, there is a decontextualized and vague process (Explore, Visualize, Analyze, Understand, Translate, and Express). The “Q” program, as it is known in our department, has been largely reduced in most classrooms to a meaningless bureaucratic shuffling of papers, whereby faculty take a couple of days to follow a prescribed worksheet. Why? Faculty have not been properly trained in qualitative thinking, and official documents offer nothing but vague and useless verbiage. Worse, most of our faculty have strong biases against math and qualitative thinking. Thus, the department assessments of quantitative reasoning have been deeply flawed with questionable validity.

Likewise, there is an important system-wide UT initiative for peer-observation to improve faculty teaching (see UTSA HOP 2.20), which is being subverted. Once again, the Chair assigned unqualified faculty to work on this program. And while the basic letter of the law has been followed, for the most part, the spirit of the initiative has been undermined, which I think constitutes another from of fraud. The leader of this initiative has no teaching experience (he was reporter before becoming a teacher a couple of years ago), and he has never done any formal study or research on education, teaching, or student learning. For many years, I have asked the Chair to develop this program into a serious endeavor to teach faculty about the science of teaching, assessment, and student learning, but she has refused to listen or do anything to develop this program. I was recently peer-reviewed by the leader of this program. He sat in on a class…and that was it. I assume he filled out the paperwork, but it doesn’t matter because this paperwork is ignored by the Chair and simply put in employee files. The exercise is currently a pointless waste of time that is of no value to the observer, the observed, or the program. Peer-observation is a vital component of faculty development, and the Writing Program has reduced it to another meaningless bureaucratic shuffling of papers.

Not only are many faculty inadequately prepared to teach, but competent faculty are prevented from teaching effectively. First of all, the Chair has mandated an unprofessional “teach-to-the-textbook” curriculum, which many faculty in the department slavishly follow because they have no original ideas about teaching or learning, let alone about the subject matter we are employed to teach. Many of our faculty do little more than follow the prescribed readings and exercises in our textbooks without fully understanding what they are teaching or why, let alone designing original curricular materials. Many faculty cannot recognize erroneous or outdated information in our textbooks, and so students get indoctrinated with useless material, which causes confusion when they are later presented with correct information in future classes. When I first joined UTSA, I gave a short lecture to the whole department criticizing the theoretical faults and factual inaccuracies in one of our main textbooks. The Chair and the rest of the department ignored my presentation; we continue to use this deeply flawed book, and most of our students get indoctrinated with some useless and inaccurate information.

Another issue that prevents quality teaching is our department’s over-reliance on student comments and evaluations, which constitute 30 percent of our yearly employment evaluations. These evaluations determine faculty raises, full-time employment, and promotion. I will demonstrate later in this report how student evaluations are invalid, discriminatory, and inversely connected to actual student academic achievement. Many faculty in our department are scared of honestly interacting with their students for fear that students will complain and their employment will be jeopardized. One junior faculty member who had been with the program for only two years confided in me that he wishes he could talk to students the way I do, but he fears student complaints, which would cause retaliation by the Chair and the departmental promotion committee.

Despite earning a PhD, the Chair has not been properly trained in information literacy, and she has shared many “fake” and predatory “scholarly journal” emails requesting faculty research for publication, which are scams that usually involve requesting money to publish. Somehow, these spam emails get through the UTSA security, which really needs to be addressed by the IT department. I had to explain to the Chair on several occasions about predatory journals and Beall’s List, which apparently she had never heard about. She was passing these emails on to the rest of the department as legitimate publishing opportunities, which I think is irresponsible and unprofessional.

Early in my career here at UTSA, the Chair also passed along an email about a summer teaching program in China. I responded to the email, thinking my Chair had actually screened emails she sent to the department and that she would only forward legitimate program opportunities for our faculty. I went to China to teach for that program and it tuned out to be fraudulent in many ways (including the altering of final grades to pass every student). I wrote a book about that fraudulent program to warn both faculty and students. I also alerted an editor at the Chronicle of Higher Education and worked with a reporter to research these fraudulent programs in China, and I was the main source of an article on the subject in that journal. A component department Chair would take personal responsibility to screen any information that is shared to the whole department because in sharing such information it can be seen as an endorsement.

The unprofessional and fraudulent practices that I have described in the Writing Program at UTSA have become commonplace in higher education. Several decades ago, Dennis McGrath and Martin B. Spear (1991) published The Academic Crisis of the Community College, which documented a disturbing trend in community colleges that has since spread to research universities, especially non-selective institutions like UTSA. McGrath and Spear (1991) argued that college classes are “conventional and mostly ineffective” (p. 48) because they “expect little commitment or effort from students and provide only meager models of intellectual activity” (p. 19). The curriculum is often “mere compilations of facts, strung together by discrete concepts within a transparent theory” (p. 30). Both faculty and students have lowered “expectation[s] about what counts as rigorous academic work” because “intellectual activity [has] bec[ome] debased and trivialized, reduced to skills, information, or personal expression” (p. 54). Faculty focused on teaching freshmen and sophomores are “disengage[d] from disciplines” and this “spawns a progressive, if silent, academic drift – away from rigor, toward negotiated anemic practices” (p. 142). Many students in America at open-door or non-selective institutions of higher education are getting a “scaled-down” (p. 93) “weak version” of college (p. 12) and a “significant leveling down of the ‘norms of literacy’” (p. 15), which limits their possibilities and sets them up for failure.

I have tried to understand this trend with my scholarship, especially my book on the history of community colleges in the U.S. (Beach, 2011), and I have tried to battle against this trend with my teaching. Unlike my colleagues, I offer high and largely objective academic standards because I am very familiar with the research on good teaching and student learning, which I will discuss at more length later in this report. Good college-level teaching should connect students to the objective world via scientific scholarship and critical thinking so that students can learn how the world works, and so students can learn real skills so they can successfully operate in the world (Gopnik, 2016, p. 180). As development psychologist Alison Gopnik (2016) documents, authentic learning takes place through concrete activities, whereby students become “informal apprentices” (p. 181) and they should “practice practice, practice” (p. 182) the specific skills the teacher introduces. Students move from ignorance and incompetence to competence, and then finally to “masterly learning,” whereby they take what they have “already learned and make it second nature” (p. 182, 204).

The teacher’s job is to explain, demonstrate, critically analyze, and evaluate students’ practice so that they can learn from their mistakes. Gopnik (2016) explains, “With each round of imitation practice, and critique, the learner becomes more and more skilled, and tackles more and more demanding parts of the process” (Gopnik, 2016, p. 185). The learning process requires a lot of work and effort, and it can be “grueling” and painful (p. 185), which causes many students to complain about the effort they have to expend. True learning is much more like the apprenticeship model found in sports and music than academic subjects (p. 186), which are more demanding practices than just memorizing information and filling in answers on standardized tests. I seek to give my students a real education along the lines of the apprenticeship model that Gopnik (2016) discussed, and I hold my students to high academic standards that push them beyond their subjective preferences towards knowledge of the objective world.

But faculty in institutions of higher education should not just be good teachers. We should also be scholars, which political scientist Keith E. Whittington (2018) defines as those who “produce and disseminate knowledge in according with professional disciplinary standards” (p. 148). As scholar-teachers, faculty should not be circumscribed by administrators and be told “what to teacher or how to teach it” (p. 142), as long as we can demonstrate professional research that legitimizes our practices. This is the foundation of free speech in the academy (p. 7), which enables universities to be marketplace of ideas. As Whittington (2018) argues, “The faculty members and staff of a university have an obligation to socialize and train students to engage in civil but passionate debated about important, controversial, and sometimes offensive subjects, and to be able to critically examine arguments and ideas that they find attractive as well as those they find repulsive. Colleges and universities will have failed in their educational mission if they produce graduates who are incapable of facing up to and judiciously engaging difficult ideas” (p. 93). As an instructor of writing, critical thinking, and argumentation, I wholeheartedly agree with Whittington (2018), and I take my mission very seriously because I know the social and political ramification if I do not.

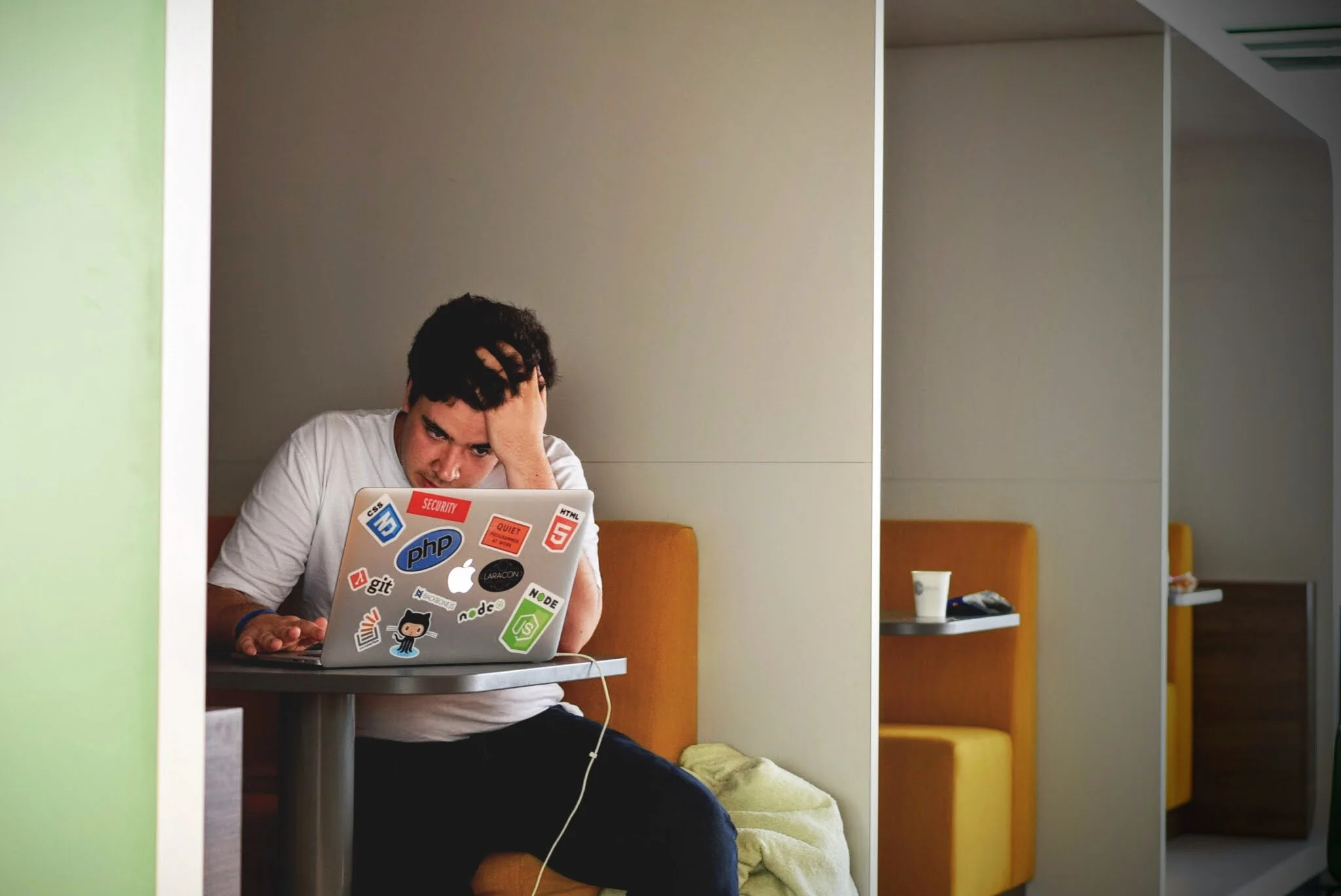

Few faculty in the Writing Program follow my example of good teaching, let alone my commitment to scholarship, disciplinary standards, and academic integrity. But I understand why. It’s easier to teach to the textbook, have low standards, and inflate grades, especially when you are working two or three jobs. My colleagues also fear the vicious circle, which is understandable: Students will complain, which leads to lower student evaluations, which leads to punitive measures, especially lower employment. Plus, there is a psychological cost for being a committed scholar-teacher. When a faculty member holds high standards, both for themselves and for students, these professional standards can cause a lot of frustration and demoralization. Professor of education Doris A. Santoro (2018) has documented K-12 teachers’ “high level of dissatisfaction” with their jobs due to widespread “demoralization,” which she defines as the “inability to enact the values that motivate and sustain their work” as teachers (pp. 3, 43). This same kind of demoralization happens in higher education. I have suffered demoralization for years at UTSA.

Many teachers, like myself, passionately care about “the integrity of the profession,” but they “cannot do what they believe a good teacher should do” because there is “dissonance between educators’ moral centers and the conditions in which they teach” (Santoro, 2018, pp. 88, 43). Santoro (2018) talked about a teacher named Reggie who had to resign after 10 years because, “You play ball or leave with your ethics” (p. 1). I know some colleagues who have had to quit UTSA (and other institutions) because they were demoralized by the dysfunctional policies and unprofessional practices. For years, I have felt the pressure to lower my standards or to just quit, but instead I have worked harder to research the problems UTSA faces, I have continually tried to discuss these with colleagues, and now I have written this report. I have always tried to stay true to my principles and best practices, and to stand up for what is right, trying to change UTSA for the better.

But I have paid a great cost over the years. I have suffered a lot of stress and worry every semester, which has caused me health problems. I have also psychologically suffered from being criticized by my peers and my Chair. I have been passed up for promotions and raises, and so I earn a lower salary than most of my colleagues, even though I am the most productive and acclaimed scholar in the department. Santoro (2018) has analyzed the “isolation” that many educators feel as “conscientious objectors” when they stand up “in the name of professional ethics” in order to demarcate the line between the “good work” of teaching from those actions that violate professional standards (pp. 8, 4). Many teachers have a “craft conscience” so when dictated rules or norms violate professional standards these teachers feel that “they are degrading their profession” by being forced to acquiesce to what Santoro calls “moral violence” (pp. 91, 138). I have acutely felt the “moral violence” perpetuated by the policies and practices of the Chair, and it has worn me down.

One issue that many teachers around the country complain about again and again is administrative pressure to pass students who do not meet professional standards by demonstrating adequate learning. I would argue that this is the biggest problem in the Writing Program, although this pressure has come from top administrators at UTSA. The Chair has repeatedly criticized me for not falling in line with the rest of the department. As Santoro (2018) documented, some teachers lament that they “damaged the integrity of my work when I passed that student” (p. 32). Other teachers have explained how they are sometimes pressured by administrators with what Santoro (2018) calls “moral blackmail,” which entails shaming teachers so they will change student grades or else face admonition or official reprimand, which could include dismissal (pp. 136, 97). I have been a victim of both moral violence and moral blackmail because the Chair has often criticized my teaching and me personally, mostly because students complain about my high academic standards, and because I fail too many students. The Chair has also used “moral blackmail” by threatening my promotions and employment over this issue. But I have staid true to my principles and best practices, and I have suffered for it.

Over the past eight years, I have raised all of these issues in one form or another, and many issues I have repeatedly raised every year. I have tried to appeal to the Chair of the department in private conversations and emails, to the main coordinating committee, and through emails to the whole department, but my ideas have been ignored, and I have often been criticized and ostracized, especially by the Chair. I have also been stuck in a Lecturer II position for years, while almost all of my colleagues have been promoted to Lecturer III, some with lots of merit pay and awards, even though they all have less experience, less education, and less professional accomplishments than I do. And worst of all, every semester I see and more and more unprepared students who can’t read and write get passed through the writing program without the skills they need to be successful in life.

Unprepared for Success: UTSA Students Lack the Motivation, Student Skills, and Academic Skills to Succeed in College

For the past eight years, I have been formally assessing student motivation and academic proficiency. I have also been studying the quality of the faculty and the curriculum of the Writing Program, as well as some of the institutional policies of UTSA. I wanted to both understand the complex causes of student failure and also to develop innovative ways of increasing student motivation and achievement. It is important to note that most of the students that I see in Writing II have already passed through Writing I at UTSA learning almost nothing, Because my colleagues inflate grades with low standards, I am put in the almost impossible position of trying to teach unprepared and largely unmotivated students both Writing I and Writing II in a 16 week semester, a difficult situation which is hard on both students and myself.

1. Attendance and Persistence, Week 1-12

When I first started teaching at UTSA I had a mandatory attendance policy, but I did not specifically reward or penalize students for coming or not coming to class, other than the right to revise one of their major essays if they missed 2-3 classes or less. I quickly noticed that absent rates were very high, comparable to what I have seen in community colleges. From 2010 to 2012, I began to document absenteeism. I found that 22% of my students missed almost two weeks of class by the 12th week of classes (about 14% of class time) and 17% of my students missed more than two weeks of class (about 19.5% of class time). Almost all of these students would end up dropping or failing because they were not in class to learn, hear directions, or stay on top of assignments.

By 2014, I not only made attendance mandatory, but I had to start grading attendance to keep more students coming to class. Almost every day there were some points to be earned by being in class and participating. Even with graded attendance, many students still missed a lot of classes, or never showed up at all. In the fall of 2016, over the first four weeks of the semester, two students never came to class. After a month, I emailed students and advisors in order to tell students to withdraw. Two other students withdrew during the first two weeks: One of these students said there was a family emergency, and the other student did not explain reason for leaving. These four students represented about 5% of the total students I had that semester.

During the first nine weeks of that same fall semester 2016, many students were coming to class late and/or not attending class regularly. Several of these students effectively stopped coming to class, although only a few students officially “withdrew” from class. I cannot teach or help students who do not demonstrate the basic student skills of coming to class prepared to learn.

Students with the most absences and late attendance, Week 1-9 (Absent/Late)

1) 6 Students: 5/0, 6/4, 4/6, 4/2, 2/3, 2/6 [2 of these students stopped attending]

2) 5 Students: 9/1, 3, 13/3, 9/2, 13/1 [5 of these students stopped attending; 1 was pregnant and got married]

3) 5 Students: 6/0, 8/0, 5/2, 9/0, 14/0 [3 students stopped attending; 1 with mental health issue]

4) 2 Students: 5/1, 8/0

5) 1 Student: 3/0 [1 student stopped attending: she was married, working 40 hours, taking 6 classes]

Students withdrawing from class during weeks 2-4 or week 8, grades for W students week 8

1) 1 (wk 2-4); 2 (wk 8): [256 points out of 365], [262/365]

2) 4 (wk 2-4)

3) 2 (wk 8): [178/365], [214/365]

4) 1 (wk 8): [197/365]

5) 2 (wk 2-4)

Analysis of Attendance and Persistence

There were two periods where students formally withdrew from the class with a “W” grade. The first period was between weeks 2-4 and the second period was around week 8. During the first four weeks, seven students had dropped. During this time and into week 9, around 20% to 30% of students in each class (except class #5) stopped coming to class regularly, were excessively late to class, or both. While attendance naturally fluctuates, some students had a pattern of coming to class late, or only attending 1 or 2 classes a week. Many students would stop attending regularly before and after major assignments.

By week 9, twelve students had stopped coming to class regularly. Of those twelve, five students formally withdrew from class by week 9, one got married and was on her honeymoon, and another student had a psychological breakdown due to personal issues. The other five students have not communicated with me and they have not withdrawn. One of these students was a serious, hard working student who had come into my office about 5 times during the first month of the semester. She asked for advice on her major, transferring to another university, internships, and also help on class assignments. But this student was married, working full-time, and taking 6 classes. We had talked about her workload, and I’m assuming that is the cause of her absents, but she never explained why she stopped coming to class (she later formally withdrew from class, and I learned that she felt the class was too hard).

How can students learn and pass a class if they are not in class, or actively engaged with their coursework? The simple answer is they cannot. Many UTSA students are unwilling or unable to attend all of their college classes, which is one of the significance causes of student failure.

Why Do Students Miss Class? Possible Causes:

There are many possible causes for excessive absences: not having prerequisite skills; succumbing to the added stress of having to learn two classes at once; poor student skills; not liking the responsibility of active learning; not liking my high standards. But I think the main cause of absents/lateness was time management: Students have too many commitments, which is the focus of the next section of this report. The majority of my students are working and/or talking 5-6 college classes. However, there were some other unique circumstances as well: One student had a mental health break-down, which took her away from class for almost two weeks, and another student was pregnant, getting married, and going on a honeymoon during the semester. Every semester I have at least one or two students who discuss serious mental health issues with me (representing about 2-3% of all my students), and many students who discuss conflicts between school and work or school and family.

2. Assessing “Soft” Student Skills, Week 1-4

For the first four weeks at UTSA, my students were graded on “soft” student skills and attendance, so I was specifically assessing specific “soft” skills. Having taught at the community college level for over a decade and having published many books and articles on community colleges, I have found that lack of student skills is one of the most significant problems causing low rates of success for community college students in terms of passing classes, persisting, graduating with degrees, or transferring to universities.

Many community colleges now require mandatory “student success” classes, which teach students the basic skills of being a successful college student, like how to read, how to learn, how to take tests, how to prioritize goals, how to manage money, and how to navigate the institution of college. In these classes, students are mostly graded mostly on participation. When I have taught these classes, students could

fail the major assignments but still pass the class if they came almost every day, participated in class, and completed almost every assignment. And yet, many students still fail the class, mostly because of absenteeism and non-completion of assignments. In the above chart, you will see that 20% to 40% of community college students failed my student success classes due to these reasons. Also, I would like to explain why one class had almost 20% more successful students. The class with a 79% success rate was at 7:30am while the other class with a 62% success rate was at 3pm. I have found that early morning classes have significantly different student characteristics than classes held during the day or evening. Generally, I have found that students who take early morning classes are more motivated and prepared.

In my UTSA classes, on top of teaching soft skills, there are also two graded academic assignments testing prerequisite knowledge from their previous course, which here at UTSA would be WRC 1013 (Freshman Composition I), but many students take this prerequisite class in high school. To be successful on these academic assignments, students needed to follow assignment directions in syllabus (also there were models of sample work in syllabus and on blackboard to help demonstrate assignments). If student demonstrated all “soft” skills, but failed the two academic assignments with F grades, then they still would have had a C+ to B- grade for class. In order to earn a failing grade of D+ or lower, a student needed to fail both “soft” skills assessments and the two academic assignments. For the first month at UTSA, my assessment was focused on:

1) Attendance

2) Punctuality

3) Effort/Motivation: Bringing textbooks/assignments to class

4) Effort/Motivation: Taking lecture/discussion notes

5) Effort/Motivation: Following directions in syllabus and asking for help

6) Effort/Learning: 2 academic assignments focused on prerequisite skills

Percentage and raw number of students failing class with D+ or lower (does not include 4 withdraws)

Class 1) 31.5% (6 students)

Class 2) 45.5% (10)

Class 3) 48% (12)

Class 4) 33% (6)

Class 5) 5.5% (1)

Analysis of Student Skills: Around 30% to 45% of students could not demonstrate core “soft” student skills, which included simply coming to all class on time with required materials and taking notes during class. This is comparable with what I see at community colleges, and in many ways, UTSA students are nearly identical with “non-traditional” community college students in terms of academic risk factors. Without foundational student skills and prerequisite knowledge, there is no way a student can pass a college class, let alone earn a degree.

Possible Causes: Poor student skills in high school; High school teacher’s not teaching soft skills; High school teacher’s teaching soft skills but not holding students accountable; 1st generation college students not aware of some soft skills (especially learning skills); Working 30-50 hours a week plus taking full load of classes; Some students taking 5-6 classes; Family responsibilities; illness

3. Assessing Prerequisite Core Skills through Essay Writing

The first major essay assignment was started week three and culminated at the beginning of week five. This essay assignment was designed to specifically target and assess prerequisite skills from previous writing classes that students needed in order to learn and master new WRC 1023 skills. These prerequisite skills have traditionally been taught in middle school, high school, and then covered at a higher level in Freshman Composition I course.

I took three class periods to discuss these prerequisite skills. These skills include basic sentence structure, basic paragraph structure, basic essay structure (topic, thesis, supporting points, evidence, and transitions), citations, plagiarism, and the “borrowing” skills of summary, paraphrase, and quoting. Outside of foundational these skills, I took another day and a half to test for reading comprehension skills, which entails finding the basic parts of writing (topic, thesis, supporting points, and evidence) in order to understand an author’s argument.

During class, students were required to take notes and ask questions about any concepts or skills they did not understand (few asked questions). This information was also assigned in two textbooks and some extra readings. I also told students to ask questions in office hours if there was any “review” information that they did not understand (few came to office hours). I repeated all of this core prerequisite information three times, once on each of these three days, plus students were supposed to read their textbooks: All concepts and skills were covered four times or more.

The first step of essay 1 was to read one source, roughly four-five pages in length. Students were to annotate this reading in order to find topic, thesis, supporting points, and evidence. Students used this information to write a summary and analysis essay, which was to be 3-4 pages in length. As mentioned, there was one and a half class periods devoted to reading comprehension in order to assess student-reading skills and help them understand the assigned text. Students worked in groups to annotate the reading, making sure they could identify the parts mentioned above. Before class, many students did not follow directions and/or they simply did not do the reading/annotation assignment. For those that did, most found the topic, but few found the thesis. Few students could distinguish supporting points from evidence/details, and most annotations consisted of random words and sentences underlined, most not part of central argument of text. Because no student could effectively read, I had to tell students the thesis and main ideas of the text, writing the basic points on board, and then requiring them to go back to the text to fully state and explain these main ideas in their own words after class.

The second step of essay 1 entailed students working groups in order to create a typed outline for their summary & analysis essay. I took 1 day of class to evaluate and grade each group outline, giving students oral and written feedback. Students then had 1.5 weeks to re-read text, revise their outline, write a draft, revise their drafts, and then hand in the final version of the essay. I specifically DID NOT take class time to discuss drafts and editing because this was a diagnostic essay assignment designed to test prerequisite skills, so I needed to see what students could do with only some guided help and review. Even after telling the students the thesis and main ideas (as described in last paragraph) and having them work together in groups on the outline, most groups still had no comprehension of the thesis and main ideas of the text. In office hours, I literally had to go paragraph by paragraph in order to read the text out loud to some students in order to explain thesis, main points, and essay organization.

This assignment was a diagnostic test to see if students knew A) how to effective read and annotate core parts of an essay, B) how to create an outline, and C) how to write a college-level summary essay demonstrating proper paraphrase, summary, quoting, and citation, and D) how to edit drafts. More specifically, I was testing for knowledge of these core concepts: topic, thesis, detailed evidence, transitions, summary, paragraph, quoting, and citation, as well as writing a basic sentence and paragraph. I was also testing to see if students can follow directions and complete work by deadlines (re-test of soft student skills mentioned above).

Before entering my class, students should have basic knowledge of ALL prerequisite skills from previous classes. However, I was not giving a true diagnostic because I explained multiple times ALL of the information they needed to be successful on this assignment. First, as I stated above, I provided students with all the core concepts four times (3 times in class plus textbook readings). Second, I provided students with models of sample student outlines and essays on blackboard. Third, I provided students with a detailed essay structure for the assignment on the syllabus. Fourth, I gave them a detailed “peer-review” assignment, which reinforced many of the core concepts. Finally, I told them the topic, thesis, supporting points, and major details of the text so they were not fully responsible for reading on their own. If students had a basic understanding of core skills, they should have been able to demonstrate all of these prerequisite skills on essay #1, especially with ALL the copious amount of help that I provided.

Percentage and raw number of students passing (C- or higher) or failing (D+ or lower) Essay 1

1) 47% Pass / 53% Fail

2) 41% Pass / 59% Fail

3) 40% Pass / 60% Fail

4) 33% Pass / 67% Fail

5) 71% Pass / 29% Fail

Majority of students do not have prerequisite skills. Where did students take Writing I class?

1) 5 UTSA WRC 1013; 3 other university; 1 community college; 8 high school

2) 4 UTSA WRC 1013; 3 other university; 1 community college; 9 high school

3) 1 UTSA WRC 1013; 2 other university; 3 community college; 14 high school

4) 6 UTSA WRC 1013; 3 community college; 10 high school

5) 2 UTSA WRC 1013; 2 other university; 12 high school

In a follow up survey the next year, I specifically asked students about their high school English classes. Almost all claimed to have earned As and Bs in high school English for both their senior and junior years. Also, 68% claimed they took AP English and 32% took duel-credit college-level English. This leads me to believe that high schools are not teaching basic skills, not even at in duel-credit classes, and that high school and duel-credit teachers are inflating grades. I have taught duel-credit college classes in Austin area high schools and I have found that many students, and in some cases most students, do not have the basic literacy skills of reading or writing. In one lower SES Austin area high school, I taught a sophomore-level class, which meant that students had already passed two prerequisite college-level writing classes, yet half of the class could not effectively read or write a sentence, let alone demonstrate higher order reading comprehension or essay writing skills.

Analysis of Prerequisite Skills:

The majority of students in four classes (53% to 67%) could not demonstrate the basic prerequisite skills needed for WRC 1023. Most importantly, the majority of my students are functionally illiterate. They cannot understand the core topic, thesis, and main ideas of a text: A) They have limited vocabulary and cannot understand all the words in a college-level text, and they do not look up unknown words; B) They cannot see, let alone understand, topic, thesis, or main points, so they “read” a text as just a jumbled list of details – They cannot see main parts of argument and how main parts are logically connected; C) They confuse details with points; D) They cannot link points and details to the person or group responsible for that information – They do not see the conversation/debate within the text, and even when this conversation is pointed out to them and explained, most quickly forget this concept.

Lack of prerequisite skills makes it very difficult, if not impossible, for many students to successfully pass my course. Having to learn WRC 1013 concepts AND WRC 1023 concepts at the same time puts a lot of stress on students. On top of this, circling back to the first issue or poor “soft” student skills, many students do not put much effort into coming to class, doing homework, following directions, understanding lectures/textbooks, asking questions, or fully completing assignments.

Given these circumstances, there is not much that I can do as a teacher. First, I have to lower standards and inflate grades; otherwise I would have to fail most of my students for not being able to demonstrate basic pre-perquisite skills. I reward students with points simply for coming to class on time, brining their books, taking notes, and for doing open-book reading quizzes. Even then, around 5-30% of my students cannot meet these basic requirements. Around 10-15% of my students (often more) can’t even make it to class consistently.

But I still hold students to a relatively high academic standard, and I force students to be responsible for information by using Socratic teaching methods. Students simply want to be “told what to do,” and then parrot the correct answer, which is not an effective way to learn. Instead, I often answer student questions with a question, trying to get them to first identify the topic of their question, and then generate their own answer by using knowledge from class lectures, notes, and textbooks. Many students find the Socratic method frustrating, too hard, and for some, rude. Why? Because I do not directly answer their questions, and I make them think for themselves. Many students do not know how to think and they don’t want to put much effort into learning thinking skills. But what is college if it is not teaching students how to think for themselves so they can be self-directed learners?

Possible Causes: The majority my students are coming from an AP class in high school or a community college. It is clear that some students were simply not taught all the basic prerequisite skills. I talked to one adult student who took Writing I in a community college, and she said she wrote four personal essays and one research paper. Most of the information that we “reviewed” in class was new to her. It is also likely that some students were taught core skills, but the teacher used ineffective methods, so skills only made it into short-term memory, and then were quickly lost. Some students do not want to invest much time and energy into the learning process: They simply want a teacher to tell them what to do. Some students are overconfident in their skills, or just unaware of how college works, because they expect that they will be able to pass all assignments without much effort.

For those who took WRC 1013 here at UTSA, all should have been introduced to core skills (although one of the essays in the norm session this semester showed that not all UTSA instructors are teaching core skills, i.e. the student with flawed punctuation and limited higher order skills who got straight As in WRC 1013). But while most WRC 1013 teachers do cover core concepts and skills, some are most likely using ineffective teaching methods, so knowledge and skills gained in class are quickly lost, and they are not retained for future courses.

4. Student Class Load and Employment

Competing responsibilities and time management are high risk factors for low student achievement and non-completion of degrees. This is amply documented in the literature on higher education students. In 2016, I took a survey, asking students about how much they work and how many classes they were taking. My working hypothesis was that many students could not manage competing responsibilities, and therefore, they simply did not have the time be successful in all of their college classes, especially a writing/thinking intensive course like WRC 1023.

Student Employment Hours: 20 hours or less / 21-35 / over 36 hours

1) 10 Students Working: 7 / 3 / 0

2) 11 Students Working: 9 / 1 / 1

3) 8 Students Working: 7 / 1 / 0

4) 5 Students Working: 3 / 2 / 0

5) 5 Students Working: 5 / 0 / 0

Student Class Load: 4 classes / 5 classes / 6 classes

1) 3 / 11/ 0

2) 3 / 11 / 1

3) 9 / 8/ 2

4) 3 / 7 / 1

5) 0 / 14 / 1