This article was a case study on Chung Dahm Learning, a private academy in Seoul, South Korea where I worked from 2009-2010. This essay is an excerpt from my book Children Dying Inside, which was originally published in 2011. In the book, I changed the name of Chung Dahm Learning to Korean English Preparatory Academy for legal purposes.

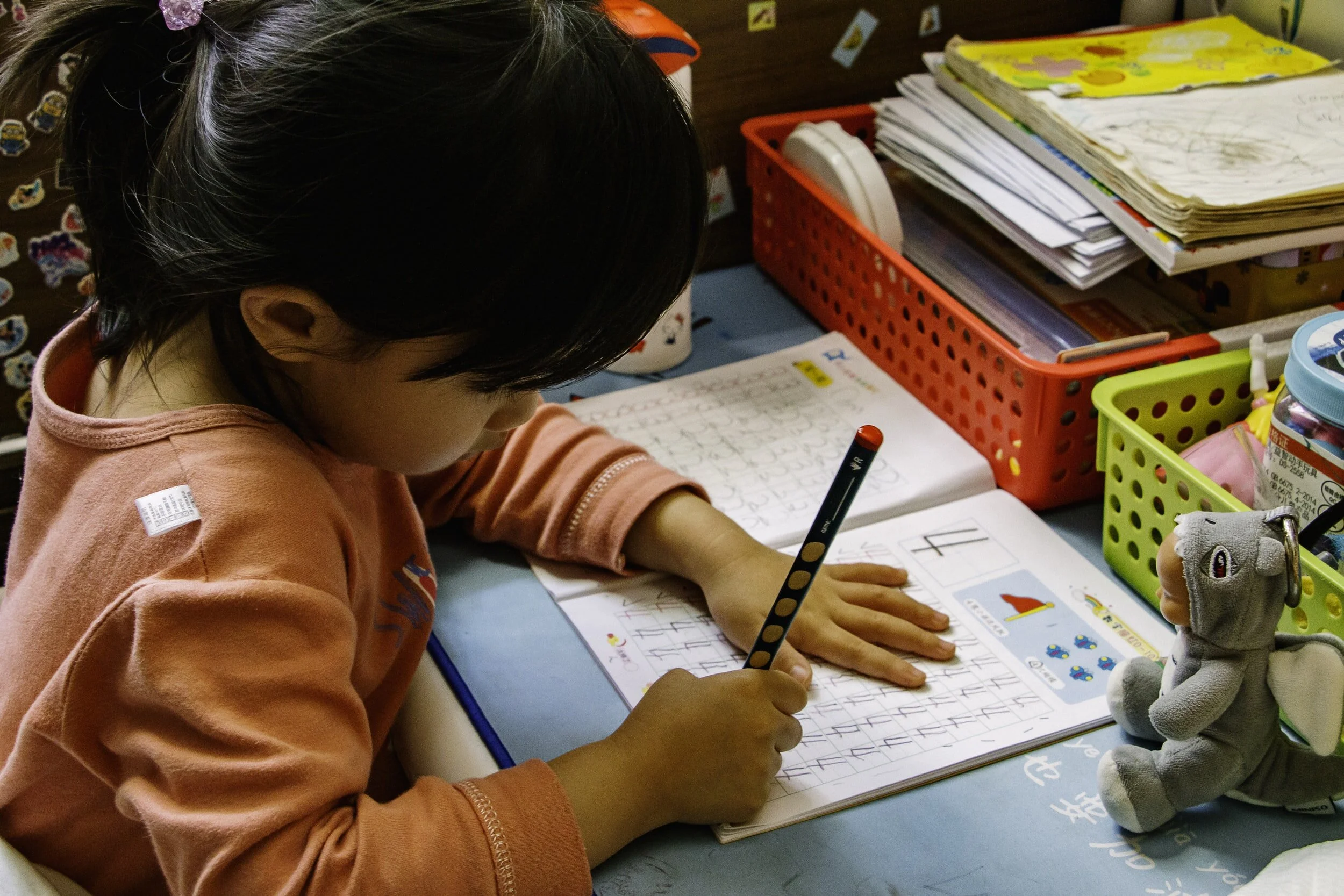

“Children die inside (test kill children)”

Private Education in South Korea

The post-war construction of public schooling was centered only on the elementary level. Middle school through university was left to private institutions with private sources of funding, mostly tuition paid by parents. Private schools constituted around 40 to 50 percent of all secondary schools in South Korea and over 65 percent of institutions of higher education. In the two major cities, Seoul and Pusan, around 75 percent of all high schools were private academic high schools and 90 percent of university students attended a private school. Michael J. Seth explained, "In general, the higher and more prestigious the level of schooling, the greater the share of enrollments in private institutions."[i]

Because of the frantic push for academic success, different forms of private schooling have dramatically increased over the last two decades in order to profit from “education fever." There are four types of private education in South Korea: private K-12 schools, private colleges and universities, private tutoring, and hagwons. Private primary schools represent a small portion of schools overall, as most students enroll in state funded institutions. Private primary schools were actually illegal until 1962 when this ban was dropped because the state did not have the teachers or facilities to accommodate the flood of students enrolling in school.[ii] Because public middle schools and high schools are non-compulsory and tuition-based, private schools occupy a large part of the 7th to 12th grade educational sector. Private schools present themselves as a quality alternative to public schooling. In the early 1990s, around 30 percent of middle school students and over 50 percent of high school students attended a private school.[iii] Seoul National University is the only prestigious public university. The rest are private schools. Thus, the vast majority of university students are enrolled in a private institution, around 90 percent overall.[iv] Outside of formal schooling there is also a robust business of private tutoring, which is legally regulated, but due to its size and highly idiosyncratic nature, it is practically free of oversight and hard to generalize.[v]

Finally, the most popular form of private schooling is the hagwon. A hagwon is a private, for-profit educational institution that delivers instruction seven days a week. The legal hours of operation are 5am to 10pm, although many hagwons open after regular school hours (3-4pm) and stay open until late at night, some past 1am.[vi] In 2008 there was a move to eliminate all restriction on hours of operation so that hagwons could stay open all night, but this measure went down to defeat, later narrowly upheld by the Constitutional Court in 2009.[vii] Hagwons enroll students from pre-school age through high school, and they come in a wide variety of forms. Many of them focus on single subject areas, like math, English, piano, or golf. There are even military-style boot camps run by retired soldiers, focusing on physical drills to test the endurance and pain threshold of students.[viii] But some of the largest hagwons present themselves as comprehensive preparatory academies, like KEPA, the focus of this study. These comprehensive academies offer a multi-leveled array of academic classes, including English, Chinese, TOEFL exam prep, literature, history, philosophy, and debate.

The primary purpose of most private education is to prepare students for the College Scholastic Ability Test (CSAT) and the Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL), which are the formal placement exams for college. The entire country adjusts its schedule on CSAT day: the government orders business to modify the work day to clear the roads for students heading to the test; all nonessential workers, both government and private, are told to report late to work; construction work near schools is halted; motorists are informed not to honk their horns; thousands of police are mobilized to handle traffic; the Korean stock market opens late and closes early; flights at all of the nation's airports are restricted; the U.S. military suspends aviation and live-fire training; and adults flock to churches to pray for their child's success. The results of the CSAT are considered the "crowing life achievement" of a student. Good scores place students in Korea's top universities, which is the primary factor in finding a good job after college.[ix]

In 1970 there were about 1,421 hagwons in South Korea, but most of these closed during the 1980s. The autocratic President Chun Doo-hwan decreed that private education was illegal so as to promote an equal educational playing field, but this ban was later ruled unconstitutional. Hagwons were legalized in a regulated market in 1991, and by 1996 private tutoring was also legal.[x] In 1980, before the ban took place, about 1/5 of Korean students received some form of private education: 13 percent of elementary school students, 15 percent of middle school students, and 26 percent of high school students. In 1997 over half of Korean students were being privately educated: 70 percent of elementary students and 50 percent of middle and high school students. By 2003 Koreans were spending around $12.4 billion on private education, which was more than half the national budget for public schooling.[xi] In 2003 about 72.6 percent of Korean students were privately educated. Parents were spending between 10 to 30 percent of family income on private schooling.[xii] By 2008 there were around 70,213 hagwons and Koreans spent almost 21 trillion won (around $17 billion) on private education.[xiii] Because the state has never funded much of the educational system, parents bear most of the burden of educating their children in the private educational market. Because of this, South Korean families spend more on education than in most other countries, around 69 percent of the total price, making the South Korea "possibly the world's costliest educational system."[xiv]

The Korean hagwon sector in particular is one of the major factors driving up the costs of education. They have begun to sell their services on the internet, thus expanding an already growing market.[xv] By the 1990s it was one of the "fastest growing of South Korea's many booming industries."[xvi] It is becoming so profitable that it has now begun to attract Western private equity firms. The Carlye Group invested around $20 million in Topia Academy, Inc., one of the largest hagwons in South Korea.[xvii] KEPA has also attracted over $2 million in foreign private equity investment.[xviii] Hagwons are also becoming a global phenomenon, following Korean immigrants abroad and attracting non-Korean students. In 2009 there were 183 academic hagwons and 73 art and music hagwons in Orange County, California alone.[xix] In 2007 KEPA spun-off a new company, KEPA America, Inc., as an independent entity with its own CEO. The mission statement of KEPA America, Inc. was to "extend the KEPA network's market to new territories like the US, Canada, Mexico, and South America."[xx]

While many Koreans consider private education superior to K-12 public education, the private sector is not without its flaws. For one, the ability to utilize private sector schooling is highly correlated to family income, which contributes to rising inequality through unequal access to quality education and through unequal preparation for elite universities. Private schools, tutoring, and hagwons serve only those who can pay, so they largely benefit the wealthy.[xxi] Hagwons also take their profit motive too far. Business practices routinely determine educational practices. These institutions inflate grades, teach to standardized tests, and place more emphasis on marketing than teaching.[xxii] It also seems that these institutions have been systematically overcharging parents for services, which promoted a rebuke by the President in 2009. The Ministry of Education, Science and Technology reported the 67 percent of hagwons overcharged, 74 percent of foreign language institutes, with more than 40 percent charging twice the standardized tuition level set by the government. But enforcement is almost impossible, not least because of the lack of government officials. In southern Seoul there are about 5,000 hagwons but only three civil servants monitoring the district.[xxiii]

Hagwons also employ teachers who have limited knowledge of subject matter and no training or experience as educators. The only qualification to teach in Korea is a bachelor's degree from a Western university, no matter the subject. Few instructors have any previous teaching experience and most know nothing of curriculum or student learning. One critic sarcastically claimed, "Business owners with suspect educational credentials seem content to hire foreign staff with equally suspect educational credentials to pretend to teach (more like entertain) children in some kind of a babysitting service designed more to generate fast profit rather than quality education."[xxiv] There have also been widespread complaints by foreign teachers that hagwons do not live up to the terms of employment contracts.[xxv]

The most serious flaw with private education, and with “education fever” more broadly in Korea, is the damage done to children. Korean culture places a lot of emphasis on exams and college placements, which creates a "pressure-cooker atmosphere."[xxvi] Thus, most hagwons use a "teach-for-the-test" curriculum that focuses on the memorization of information, standardized multiple-choice tests, and test-taking techniques. Diane Ravitch has insightfully critiqued such high stakes testing where the curriculum is reduced to "test-taking skills:" Students "master the art of filling in the bubbles on multiple-choice tests, but [cannot] express themselves, particularly when a question requires them to think about and explain what they had just read."[xxvii] Linda Darling-Hammond has also noted the limitations of standardized testing: "Researchers consistently find that instruction focused on memorizing unconnected facts and drilling skills out of context produces inert rather than active knowledge that does not transfer to real-world activities or problem-solving situations. Most of the material learned in this way is soon forgotten and cannot be retrieved or applied when it would be useful later."[xxviii]

With such a curriculum students are "trained, not educated,"[xxix] and this training rewards students for endurance and trickery, not learning. Korean students rarely understand the information being taught to them, they are not taught to critically analyze information, and they cannot apply information to other contexts. Students simply become "expert memorizers" of "de-contextualized" facts that can only be used to take standardized tests.[xxx] This teach-for-the-test curriculum "stifle[s] creativity, hinder[s] the development of analytical reasoning, ma[kes] schooling a process of rote memorization of meaningless facts, and drain[s] all the job out of learning."[xxxi] High stakes exams also lead to widespread cheating, grade inflation, and outright bribery.[xxxii]

But there is a much more serious problem for students. Hagwons take up a lot of extra time for classes and homework, add additional pressure for academic performance, and induce more stress on already overburdened students. Students already spend a lot of time studying for regular school exams, but the addition of hagwons and private tutors takes up a lot of time during the week, leaving most students with little to no free time. Students routinely are in school, studying, or engaged in private education for up to 18 hours a day, seven days a week. One student explained, "I have to get up at 7 in the morning. I have to be at school by 8 and lessons finish at 4. Then you go to a hagwon and when you arrive home, it's around 1 o'clock in the morning."[xxxiii] The Korean Teachers and Education Worker's Union claims that high school students sleep on average 5.4 hours a day, although a recent academic study found that the average sleep time was slightly higher, around 6.5 hours a day.[xxxiv] The Ministry of Health, Welfare and Family Affairs has issued warnings about student's irregular meals and lack of sleep. About 40 percent of elementary and middle school students skip meals because they lack a break in their busy daily schedule.[xxxv] There is a popular student proverb, "If you sleep for four hours a night, you'll get into the college of your choice - if you sleep for five hours, you fail."

This pressure to perform leads to serious physical harm and psychological distress. Parents and teachers routinely beat students that do not perform well academically. A study published in 1996 found that "97 percent of all children reported being beaten by parents and/or teachers, many of them frequently."[xxxvi] Many students turn to suicide as the only escape from this relentless pressure to perform. Statistics are not routinely kept on this issue, but limited data are frightening. Around 50 high school students committed suicide after failing the college entrance exam in 1987. An academic study published in 1990 revealed that "20 percent of all secondary students contemplated suicide and 5 percent attempted it."[xxxvii] And the problem is only getting worse. Two recent surveys found that between 43-48 percent of Korean students have contemplated suicide. From 2000 to 2003 over 1,000 students between the ages of 10 and 19 committed suicide. Families also suffer. In 2005 a father was so distressed over his son's bad grades that he torched himself, his wife, and their daughter outside his son's school in shame.[xxxviii]

The Business Model of KEPA: Organizational Structure and Mission

Korean English Preparatory Academy was founded in 1999 by a private English language tutor. It began as a small private school with only a few instructors. Now it is a publically traded corporation in the “education industry,” and one of the most prestigious hagwons in South Korea. KEPA has over 250 instructors and hundreds of staff on 65 campuses spread across Seoul and every major city in Korea. Citing the success of Coca Cola and McDonalds, KEPA has also initiated the “globalization of our business” to capture a share of the international ESL market. Towards this end KEPA has initiated a joint venture with a group from Zhing-Hwa University in China. KEPA has also spun off a separate corporate entity, KEPA America, Inc., which was designed to export the hagwon model to the American continent. And KEPA created an English language immersion school in British Columbia, Canada.[xxxix]

KEPA has an integrated ESL program broken down into multiple levels, beginning with a very basic introduction to the English language for pre-school age children, all the way to college-prep history, literature, writing, and debate classes for high school students. Placement in every level is determined by a standardized test with incremental scores correlated to the different course levels, ranging from a score of 0-31 for the introductory level to a score of 110 or higher for the college prep classes. Outside of the academic “fundamentals,” there is also a structured program designed solely to train students for TOSEL based standardized tests, including grammar, reading, multiple choice question types, essay writing, and interview questions.

KEPA uses a range of textbooks from Cambridge University Press, Pearson/Longman, Scholastic, Cengage, and a series of specially designed KEPA workbooks designed by their in-house research and development center. KEPA also has a national corporate website to centralize teaching materials, on-line student homework, attendance, and grading.

In corporate advertising and outreach materials, KEPA presents itself as a college preparatory academy with professionally trained teachers and a 21st century curriculum. Corporate advertising routinely pictures the same image: an ordered classroom setting with uniformed students actively engaged with energetic teachers wearing suits and ties. Outreach materials are professionally and fashionably designed in full color on expensive paper. These materials break down the curricular aims of the academy through trendy catch-phrases, like “critical capability” and “communicative capability.” The “critical” component is broken down into “critical reading/listening” and “critical speaking/writing,” with each part further packaged into three broad student outcome “deliverables:” “English fluency,” “knowledge,” and “critical thinking.” The “communicative” component focuses on the interactive process of classroom instruction, which includes class discussion, debates, group work, research, group presentations, peer evaluations, “skill” training, online instruction, and webzine postings.[xl]

The CEO of KEPA has positioned his company in response to his perception of the global economy. He points to three highly abstract macro-economic developments, "the globalization trend," the "information revolution," and an "economic crisis that arose in the last 50 years." He states that these macro-economic changes have produced a "paradigm shift" in global and national markets, which in turn has created demand for a new set of skills. Thus, the CEO created KEPA to capitalize on these developments, selling the "skills" students will need to compete in a globalized world and to protect themselves from "economic crisis."[xli]

What are those new skills? The CEO identified only two: "English expression" and "critical thinking." To impart these two skills, the CEO created a new "methodology" that would focus on both skills from "the beginning" of language training, thus, creating a "blended learning system" that would "amplify learning efficiency." The CEO vaguely explained, "The Critical Learning system is a new attempt to accomplish the learning objective through the merger and improvement of system and contents." This learning system also blends classroom instruction with "on-line learning," which includes grammar exercises, writing, and a national blog to post projects and comment on classroom assignments.[xlii]

While language acquisition is fairly straightforward, what is critical thinking? The CEO defines this practice as "disregarding intuition and emotion" in order to use logic to solve problems via a "topical approach." At a basic level, logic is the ability to understand main ideas "while avoiding comprehension of minor details" in order to "execute an oral or written summary." At a higher level, logic is an "attempt" at "in depth comprehension" by analyzing "purpose," "tone," and "identifying logical fallacies." The topical approach is explained simply in terms of learning language through the study of a specific informational topics, such as endangered species, cloning, or cyber bullying.[xliii]

What is the "learning objective" for KEPA? This is somewhat unclear. The CEO has described the KEPA mission in very vague and abstract language: "Cultivating communicative capability by escaping from self-rationalization, which can be a blind spot of critical thinking, and reinforcing resolution through compromise." Another corporate document uses equally abstract but more humanistic terms, "Our mission is to help people realize their potential and thereby discover new meaning in their lives."[xliv] In the more concrete terms of classroom methodology, students learn vocabulary and grammar through reading or listening to a specific topic, while they practice speaking skills. The culmination of each classroom activity is a "critical thinking project," which is a group project that is supposed to demonstrate "solving problems" through "discussion, evaluation, and the logical presentation of an organized conclusion."[xlv]

In a widely disseminated image used in teacher training meetings, KEPA explains its organizational mission in terms of a bowl of rice. The rice is critical thinking, and just like rice, critical thinking is "necessary for survival." The bowl is the "delivery system," which is a combination of internet technology and faculty. The role of teachers is to "deliver" the product of "critical thinking." However, the rice is also presented in a different slide as a trio of knowledge goals: critical thinking, cognitive language, and relevant content. This is the official trio of the Korean Association for Teachers of English (KATE).[xlvi] This image reveals KEPA's basic content-centered pedagogical framework: the "banking concept of education." Knowledge is an object that the teacher holds and "deposits" into the passive "receptacle" of a student.[xlvii]

While KEPA markets itself as an educational institution, internal documents and the CEOs own language paint the organization as a profit seeking business. In an internal corporate magazine, KEPA Culture, the CEO of the company made it clear that the most important part of KEPA’s success was the “self-confidence and invincible attitude to maintain market leadership,” including the ability to diversify the company to reach multiple markets in the private education sector. Corporate leadership does not discuss teaching or curriculum in educational terms. Instead they refer these parts of the business as “products” and “contents.” The company is not focused on any academic or learning principles. Instead administrative leadership discusses their corporate mission in terms of an “ESL lifestyle business.” As such, this organization is focused on launching “new products” to generate revenue, creating “strategic marketing campaigns” in order to “create value,” becoming a “content leader” in their niche, and muscling out other ESL “competitors” to capture greater market share.[xlviii] In internal documents, the CEO primarily refers to KEPA as a “publically listed company.” He calls KEPA a “corporate organization comprised of business divisions, R&D centers, and performance-driven IT and management infrastructures.” Different campuses are referred to as “franchises” and “subsidiary companies.”[xlix] There is rarely any mention of teaching, learning, or curriculum, and never any attempt to characterize KEPA as an educational institution. As far as corporate leadership and administrative staff are concerned, KEPA is a profiting seeking business.

After sorting through corporate memos, teacher training presentations, administrative staff comments, and teacher comments, it is clear that KEPA sends mixed messages about the multiple and often highly abstract objectives of this organization.

Most administrators and teachers have no clear idea about what the company stands for or what to prioritize in the classroom. It is clear that KEPA has lofty business and instructional goals, but the corporate vision does not fully connect with the more concrete methodology employed in the classroom. Further, due to the vast confusion over organizational goals, most staff go with whatever corporate directive has been most recently issued, while adhering to the monolithically proscribed instructional routine for classroom management. Thus, despite the lofty rhetorical goals KEPA espouses in outreach documents, corporate memos, and teacher training seminars, the real organizational emphasis of this company seems to fall on two interlocking objectives: making profit while rigidly adhering to the KEPA "delivery system."[l] The later is a teacher-proof curriculum and classroom management structure known internally to teachers and staff as the "KEPA method."

Teaching without Teachers: Authority, Structure and Surveillance

Externally, KEPA advertises itself as a state of the art English language academy with professionally trained teachers, a 21st century curriculum, and engaged students. Internally, corporate executives claim to have created a new ESL curriculum that is supposed to train students to become proficient in the English language (listening, speaking, reading, and writing), as well as in critical thinking and argumentative debate. However, behind the corporate rhetoric lies a different, darker reality. Only vaguely understood by most organizational actors, there is an institutionalized "hidden curriculum"[li] created by KEPA's CEO and organizational structure that undermines KEPA's corporate rhetoric and frustrates student learning.

The CEO wants to make KEPA a “united” organization with a “central focus.”[lii] As one middle manager explained, "It is crucial that we all 'row this big ship together for smoothing sailing.'"[liii] But to maintain order and discipline, the CEO admits that he has to use an “authoritarian” management style and to be “strict on the staff and faculty.”[liv] Why? Because KEPA employs an inexperienced, untrained, and transient workforce.

Most middle managers, administrative staff, and instructors leave the company within a year. Some middle managers leave the company after only three to six months. At my particular branch, four different people occupied the upper-middle manager position and three different people occupied the lower-middle manager position within twelve months. Few entry-level administrative staff have any knowledge of English or education, and most cannot even speak English. These low-paid, primarily young office workers rarely stay for more than six to nine months. All of the English instructors are recruited from overseas on one-year contracts, and the majority stay for only a single year. If an instructor persists for more than a year then they are automatically considered an "expert instructor."[lv] Most of these instructors have only a bachelor’s degree in fields other than English and no previous teaching experience or knowledge of student learning. Some have extremely limited reading, speaking, and writing skills and they are not fit to teach. Most if not all instructors are employed at KEPA because they could not find employment in their home country. Some come overseas to primarily "party," while waiting for a better opportunity back home.[lvi] For the majority of instructors, working at KEPA is all about the money, and for the most part, KEPA pays a higher wage and offers better working conditions than many other Korean Hagwons. Given instructor's lack of skills, inexperience at teaching, and mercenary motives, combined with the traditional hierarchical culture of Korean corporations, the CEO's decision to maintain an "authoritarian" organization seems reasonable. To deal with an unskilled and transient workforce, the organization is built on the foundation of authoritarian managers who enforce a rigid classroom management method. Instructors and administrative staff are but the interchangeable and temporary "bowls" delivering the standardized product that makes KEPA a hefty profit.

The KEPA instructional method is a carefully guarded "confidential" trade-secret that was created by the CEO and developed by the Research and Development staff. Only top corporate managers, R&D staff, and Training Center instructors have full access to the rationales behind the KEPA method. All middle management and instructors are given a brief, standardized version of the KEPA method, which is a "class structure" that must be rigidly followed. Instructors are not told how or why the method works. They are simply told to follow the method. Every three hour class has the same standard format and is planned down to the minute. Instructors are told to follow the "class structure" without question and without modification. The main task of middle-management is surveillance. They monitor instructors via CCTV to make sure every part of the "class structure" is accomplished according to a standardized "observation report," which is a checklist based on the "class structure," with the addition of three additional factors, enthusiasm, professionalism, and student management. But the main rubric that all middle management cling to and incessantly enforce is whether or not an instructor "follows KEPA methodology for class structure and instruction," which means does an instructor do each prescribed activity on the checklist for the exact length of time allotted for each task.[lvii]

The KEPA method is the centerpiece of the organization. The CEO claims that the KEPA method is a "new product" that has enabled KEPA to become a "content leader" in the ESL market.[lviii] The KEPA method is not only a "new" and effective way to teach ESL for the 21st century,[lix] it is also "the most effective ESL methodology in East Asia."[lx] On what does the CEO base his claims? What knowledge or training does the CEO possess to invent such a revolutionary educational model? The answer to both questions, sadly, is nothing. The CEO earned a bachelor’s degree in philosophy. He mostly focused on G. W. F. Hegel, the German romantic who believed the world was infused with transcendental spirit, and the CEO is prone to sending Hegelian inspired, abstract emails to faculty and staff. After working for a number of years as a private tutor, the CEO was able to start his own hagwon business. He seems to think of himself primarily as an entrepreneur, not as an educator, and he refers to KEPA primarily as a business. After starting the company, he hired a number of program marketers and researchers that helped him invent and market a "new" ESL product. But these program developers only had bachelor’s degrees, mostly in fields other than English or Education. According to one former R&D staff member, these people had almost no knowledge of the disciplines of English, English as a Second Language, or Education, yet they were designing the curriculum.[lxi]

So, if the method was not created by knowledgeable ESL or educational experts, then what is the KEPA method based on? I was able to get a copy of the "confidential" General Trainer's Manual through an informant. This official document is the company Bible because it contains the complete curricular rationale and framework for the KEPA method. This Manual was developed by the CEO, R&D, and program marketers, and it is only given to the elite, veteran KEPA instructors who are company certified to train incoming recruits.

The 45-page Manual contains only 12 pages of conceptual framework. Many pages present information that has been plagiarized, and only 6 pages contain 18 partially documented secondary sources. Of these sources, 17 are cited as either an author's last name or in parenthetical notations with an author's last name and year of publication. There is no bibliography, and only one title is presented. The one fully sourced reference is improperly placed in the middle of a page between two summary paragraphs. Despite some citations, there is no indication that these references are used with any professional or academic reasoning. No author's academic credentials, discipline, or expertise is mentioned. There is no discussion of research methodology and there is no critical analysis of research findings. All references are cited at the end of brief summaries (most are one sentence long), which present a list of generalized knowledge claims. All of these generalizations are superficial and display no substantial understanding of the subject matter (such as student self-efficacy, student behavior, or student learning). Some of the generalized claims are simply nonsense: "A cognitive phenomenon strongly supported by psychological research, has broad applicability within education." There is obviously no knowledge of professional academic standards on plagiarism, summary, critical analysis, or referencing, let alone any expertise in the content of ESL education or student learning. The few authors that are named are referred to generally as "professors," which seems to lend a general aura of credibility and authority to the claims being presented. But these claims are presented randomly in a list with no overarching thesis, integration, or coherence.[lxii]

The single most repeated and authoritative source cited in the Manual is the CEO. In Asian corporate culture, leadership is revered. The CEO of KEPA is treated like a demigod. When he makes his yearly appearance at each branch the entire staff lines the entrance to greet him. Every corporate email or memo is treated as revealed truth. But a close inspection of his unfounded and illogical claims in the Manual shows that he is no expert on education, ESL, or anything else. The CEO claims that East Asian ESL speakers are very different from "other ESL regions" because only East Asians use English for "business and academic communication." Thus, he claims there is a specific need for a "distinctive" East Asian ESL method for these purposes. Furthermore, he claims to have invented "the most effective ESL methodology in East Asia." On this foundation, the CEO defines several key concepts and makes several knowledge claims that form the foundation of the KEPA curriculum. This information is presented as self-evident truth and there is no attempt to reasonably explain any concept or claim, let alone conclusively proving them true.

The Manual violates every elementary principle of expository writing, logical analysis, and critical thinking. Superficial and abstract knowledge claims are randomly strung together in lists with no thesis or coherence, and the whole document is grounded on a fallacious appeal to the authority of the CEO and the KEPA corporation. In this regard, the section on critical thinking is highly ironic. It tells the reader that "'Critical Thinking' is most essential to KEPA ESL Methodology." It warns against "dogmatic thinking," which is defined as "accepting one perspective blindly," and just "reiterating" a single perspective as truth. Yet in defining and explaining critical thinking, this document merely quotes the CEO from a marketing memo and then ends with a long quote from late 19th century proto-sociologist William Graham Sumner, who is referred to authoritatively in the present tense as an "American academic and professor at Yale." The General Trainer's Manual is transparently an exercise in uncritical, dogmatic thinking. It presents a highly selective, superficial, disorganized, and unfounded list of incoherent information as "the most effective ESL methodology in East Asia," and new recruits are sternly told to follow it to the letter.

Perhaps the most telling aspect of the General Trainer's Manual is the fact that only 12 out of 45 pages are devoted to any type of content-based information on ESL, student learning, or instruction. The rest of the Manual is a prescriptive checklist. It follows the same rigid logic as the standard classroom KEPA method and it is consistent with the overall authoritarian ethos of the organization. The Manual tells the trainer exactly what to do every day of training down to the minute. There is a regimented "Training Check List" to follow for every component. It even tells the trainer how many new recruits should fail the program (10%). But of course, the final outcome of training is not controlled by the actual trainers. All pass/fail decisions are made by the Director of the Training Center who receives trainer recommendations and reviews all training sessions via CCTV. This training structure is similar to the general management structure of KEPA where a large group of middle managers watch CCTV to monitor and evaluate staff. But when it comes to final evaluations, disciplining, rewarding, or firing staff, only corporate managers have the real power to make decisions.

Many instructors put up with this rigid structure because of the pay, and because of the "upward advancement opportunities" to "climb the corporate ladder." Like other Korean corporate organizations, KEPA prizes loyalty above competence. Almost all senior administrators and middle managers worked their way up from being an instructor, which is seen as the entry position to earn one's place within the "business culture" of KEPA.[lxiii] Others stay on because it is an easy job with good hours (4-10pm), relatively good pay, and most instructors only work four days a week. These instructors have plenty of time and money to pursue a range personal activities and to explore a fascinating foreign culture. Some find working with ESL students very rewarding and a few say they want to be teachers upon returning home. Finally, some instructors buy into KEPA's corporate rhetoric and find this organization a worthwhile and satisfying experience. As one instructor explained, "I picked up valuable skills...diversifying my experience at KEPA. I was selling a product that I actually believed in... teaching."[lxiv]

"Children Dying Inside": Instructional Ritual and Student Resistance

To deal with an unskilled and transient workforce, the organization is built on the foundation of authoritarian managers who enforce a rigid classroom management routine called the "KEPA method." Almost every three hour class follows the same basic structure and each activity is rigidly planned down to the minute. This class structure is repeated for 9 weeks, on the 10th week a standardized achievement test is administered (speaking, reading, listening, and writing), and then the 11th-13th weeks are back to the normal routine. Every three month term follows the exact same structure, and there are never any breaks between terms.

Except for the college prep courses, every class follows the same basic routine. The first five minutes is attendance and homework review. The homework is a combination of vocabulary exercises, filling in blanks, and writing a paragraph summary. Grading homework consists of a quick glance at a workbook to make sure all blanks are filled in (there is no inspection for understanding or accuracy). Students earn an A+ if all homework is completed and an F is nothing is done. If at least some blanks are filled then they earn a B. These are the only three grades an instructor is allowed to give. Next is a "review" test on vocabulary. Students are assigned 45 vocabulary words, 45 synonyms, and 10 phrase length "chunks" to memorize each week. The average score is 50 percent (10/20 questions), which earns a B grade. A score of 10 percent (2/20 questions) earns a C- grade. These grades are set by R&D. Then there is a 10-minute-long whole class "student counseling" discussion, in which instructors explain homework, "motivate" students by publicly recognizing high performers and scolding low performers, and if there is time, conduct "student rapport" activities, such as language games, like 20 questions, telephone, or riddles. The next two hours are devoted to a brief skill lecture and then reading or listening exercises, leading up to a reading or listening comprehension quiz. The final activity of each class is a group "critical thinking project" based on the day's content theme. Students are given prompts and asked to prepare a group oral presentation, which they will speak in front of the class. The class is supposed to evaluate each group and a winning group is chosen by the instructor.[lxv]

On the surface, this basic structure seems to pack a range of language-based activities into a well-organized three-hour block. Time is given to vocabulary, skill acquisition, skill practice, skill test, writing, group work, and oral presentations. And in fact, high performing students are able to use this structure to practice and polish their English skills. However, there is almost no time for individual feedback or correction, thus, there is very little opportunity for students engage the material and learn new skills. Furthermore, KEPA's curricular materials are inappropriately advanced for most students, thus, students struggle to understand the lesson's conceptual topic and advanced vocabulary words. Elementary students in the basic reading and listening programs are taught about beneficial bacteria, hyperinflation, competing scientific theories of species extinction, or cryogenics. In the more advanced classes, elementary and middle school students use American college textbooks with sophisticated essays and they are introduced to logic, argumentation, fallacies, and expository writing. Most students are completely overwhelmed, not only by the advanced conceptual topics, but also by the extremely advanced vocabulary. The majority of students in every class routinely fail the reading or listening comprehension quiz. The average score hovers around 50 percent or lower. Students struggle to comprehend the material thrown at them each week, let alone developing their language skills.

The KEPA pedagogical structure itself is to blame. Due to the rigid time and activity structure, there is no opportunity for instructors to explain each week's topic, nor is there any time for the class to engage in discussion. The whole focus of the class is preparing students to take the standardized multiple choice question test during the second hour, which is meant to prepare them for the standardized final exam week 10. In fact, the whole KEPA curriculum is built around the College Scholastic Ability Test (CSAT) the Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL), and a host of other standardized tests, which are the formal placement exams for academic high schools and colleges. Despite KEPA's rhetoric about language acquisition, blending learning, and critical thinking, this hagwon is only concerned about one goal: preparing students to take standardized tests in the English language. Thus, the primary instructional activity that KEPA management places at the center of the KEPA method is "test-taking skills." In training secessions and from management comments, the primary instructional activity is to help students "refine fundamental test-taking skills" so that they can "obtain the best iBT score possible." This is the central mission of KEPA. Classroom activities focus not on discussion or understanding written texts or oral texts, instead they focus on standardized test question types, strategic approaches to text taking, note taking, and summary writing. This also explains the difficult nature of the textbooks because TOEFL and other standardized tests use "excerpts from college-level textbooks." Thus, students read or listen to college-level texts, not because it is developmentally or educationally appropriate, but because it is necessary to acclimatize them to standardized test taking.[lxvi]

There is no room in the KEPA method to make weekly topics interesting, relevant, or even understandable to most students. This alienates and frustrates even willing students. But most classrooms are not filled with willing students, especially when they reach middle school. There is an underlying reality behind Korean private schooling: it is culturally mandatory. Because of the general "education mania" in Korea, parents enroll students in private education all week long. Some students go to hagwons and private tutors seven days a week for up to six to eight hours a day. After an informal class discussion on how students are overworked in Korea, I had one of my students approach me after class. He informed me that he has to go to 13 hagwons a week, each assigning homework, plus his regular school and homework. He said he had no choice. His parents make him go. Many students report that they are always going to hagwons or doing homework, they have no free time, and they sleep only four to six hours a night.

Thus, many students in KEPA classrooms are completely unresponsive and do the very least just to get by because they know schooling is simply a test of endurance, and they how to work the KEPA system. As long as students fill out their book, stay quiet during class, and do at least some homework then they will earn passing grades. Many students will just stare at the walls during class. The week 10 standardized achievement tests are also rigged to accommodate these unresponsive students. The same tests are used over and over again, grading is curved, and students will advance to higher classes if their parents complain. KEPA offers a highly ritualized environment that demands very little from students other than displaying the proper behavior. There is a subtle truce between instructors and students. Many students play the hagwon game to keep up the appearance of schooling; however, a close look into their blank eyes reveals a silent, enduring resistance. Sometimes this resistance turns into open hostility. One student explained, there is "conflict between teachers and the students which leads to an uncomfortable learning environment."[lxvii]

I engaged students often about their educational circumstances in order to understand how they perceive schooling, hagwons, and the pressure to perform. 92 percent of the students I surveyed (n = 59) said they went to school 6 days a week, while on average spending just over 5 days a week at private education (either a hagwon or a tutor). 19 students (32%) spent 7 days a week at private education. Students averaged about 4.2 hours a day at private education, with 6 students (10 %) spending an average of 7+ hours a day at private education. On average students went to 4 different hagwons or private tutors, with 7 students going to 7+ hagwons or private tutors. On average students spent 4.2 hours a day on homework, although over 20 percent said they spent 7+ hours a day on homework. When asked how much "free time" students had during the day, the average response was 2.5 hours, with 39 percent responding only 1 hour. On average students got 7.6 hours of sleep a night, with 15 percent saying they got only 5-6 hours of sleep.

I also asked students to write about what they liked or disliked about the hagwan. Most students repeat the same basic evaluations: too much homework, too many tests, too much stress to perform, and not enough break time to eat and go to the bathroom. On student wrote, "They spend lots of time in doing KEPA homework, no time to do school homework, and no time to study other subjects." Most disturbingly were the repeated comments about how much "stress" all the class time, homework, and tests put on students. One college prep student wrote, "The Korean school system puts too much pressure on students. The stress that the students have to carry on their backs is very heavy that some students fall down, never reaching their goals. Do we have to do it this seriously? I absolutely DON'T think so." Another college prep student wrote something similar, "Everyday I have to go academies... every day I have to finish homework...I get tired, stressed usually, when I am busy. I am hated of doing this uninterested thing...Usually I feel negative of this busy life. But I'm continuing this life because I'm being forced." Two elementary students verbalized in quite shocking language how this stress makes them feel: "Children dying inside" and "Children die inside (test kill children)." A couple of students said they "hate" KEPA and want to "destroy it."[lxviii]

Conclusions

Taking the ethical vantage point of Amartya Sen's "impartial spectator,"[lxix] I want to make a few observations about the South Korean pursuit of "education fever" and the social role of hagwons, like KEPA, in order to ask a basic question: Is the South Korean educational model just or fair? Specifically, I want to use Sen's "capability approach" to look at the means and ends of "satisfactory human living" and the extent to which an individual not only "ends up doing," but also what that individual is "in fact able to do" and whether or not that individual is able to freely choose any particular course of action.[lxx] As Sen explains, "A theory of justice - or more generally an adequate theory of normative social choice - has to be alive to both the fairness of the processes involved and to the equity and efficiency of the substantive opportunities that people can enjoy...Neither justice, nor political or moral evaluation, can be concerned only with the overall opportunities and advantages of individuals in a society."[lxxi]

The ends of South Korean education look very attractive. Today, South Korea has one of the highest percentages of school-age population enrolled in both K-12 and higher education, around 99 percent enrollment in middle school, over 96 percent in high school, and close to 70 percent in some form of higher education.[lxxii] South Korea has also been the site of a "miracle" socio-economic transformation from an underdeveloped, autocratic third-world backwater into a developed, free-market, high-skilled economy and democratizing society. South Korea deserves credit for its highly educated population, soaring industrial productivity, and innovative technology, but at what cost and who pays the cost?

In 2008 Korean families spent almost 21 trillion won (around $17 billion) on private education.[lxxiii] South Korean families spend more on education than in most other countries, around 69 percent of the total price, making the South Korea "possibly the world's costliest educational system."[lxxiv] And students are pushed from as early as kindergarten or the 1st grade to not only perform well in regular schooling, but also to go to private tutors and hagwons so that they can prepare for the high stakes testing in middle school, high school, and the college entrance exam. Most students study all day for seven days a week and get less than eight hours of sleep a night. These students are pushed to study and succeed on standardized tests, they are pushed to become fluent in English, and they are pushed to get into the most prestigious high schools and universities. Students are slaves to their parents' ambitions, whether or not some students actually internalize "education fever." Students are under so much pressure that a large percentage of students, somewhere between 20 to 48 percent, actively contemplate suicide each year, and a significant minority actually kill themselves because they cannot take the pressure to succeed or the burden of failure.

And what are South Korean children actually learning in this "pressure-cooker atmosphere"?[lxxv] Public and private schools use a "teach-for-the-test" curriculum that focuses on the memorization of information, standardized multiple-choice tests, and test-taking techniques. Korean students rarely understand the information being taught to them, they are not taught to critically analyze information, and they cannot apply information to other contexts. Students simply become "expert memorizers" of "de-contextualized" facts that can only be used to take standardized tests.[lxxvi] This teach-for-the-test curriculum "stifle[s] creativity, hinder[s] the development of analytical reasoning, ma[kes] schooling a process of rote memorization of meaningless facts, and drain[s] all the job out of learning."[lxxvii]

And what are the ends of this education system? Students are ultimately competing for a limited number of high paying jobs with top corporations or government agencies. But economic and social inequality has intensified over the last several decades, and there is “a growing disparity” between rich and poor measured by consumption patterns, residential segregation, and access to quality education, especially quality higher education.[lxxviii] Not only are the numbers of impoverished and underemployed still a problem, there has also been increasing unemployment and growing job insecurity for white collar workers. Women still find it hard to compete in the labor market. Over the past decade, Koreans have suffered setbacks from less protective labor laws, increased competition in the skilled labor market for fewer full-time jobs, and the introduction of neoliberal business models, like increased use a flexible, contingent, and low-paid labor force that can be easily hired and fired in reaction to business cycles.[lxxix] Plus, the educationally driven culture of South Korea turns out many more college graduates than can be adequately employed in the economy.[lxxx]

But schooling in South Korea has traditionally been about social status and class, not employment in the labor market.[lxxxi] Koreans have had a "faith in education," seeing it as the only avenue to social advancement, if not economic opportunity.[lxxxii] A successful student not only raises his or her own status, but also brings social benefits to the entire family. Thus, Denise Potrzeba Lett has argued that economic goals are not "the primary motivation" behind Koreans' pursuit of education. Instead, Koreans' "pursuit of education was more than anything else a pursuit of status."[lxxxiii] Lett calls the modern manifestation of the process the "yangbanization" of Korean society: "as South Korea's middle class has become more affluent, it has come to exhibit characteristics more typically associated with an upper rather than a middle class."[lxxxiv] The pursuit of formal education, especially higher education, becomes the primary marker of class distinction, which helps position an individual within the highly regimented labor market.[lxxxv]

The ends of the South Korean education system seem perversely clear: a successful student spends 16 years of intense intellectual labor, earns a degree from a prestigious university, and gains entry to one of the top 50 corporations, only to raise a family and push his or her children onto the same path. But only a minority of South Korean students actually fulfill this career trajectory. In a society defined by social status and the attainment of success markers, what is the quality of life for the majority who fail to reach the cultural pinnacles of success? And is educational, social, and economic success truly just if it is not freely chosen?

And even if one of the lucky few achieve all of these markers of success, what then? Are they happy, fulfilled, content, complete?

I am reminded by the words of the French philosopher Pascal: "The present is never our end. Past and present are our means, only the future is our end. And so we never actually live, though we hope to, and in constantly striving for happiness it is inevitable that we will never achieve it."[lxxxvi] South Korean society is obsessed with status and education seems to be the primary vehicle to attain this future end. But if the process to obtain a desired end causes only misery than what happiness can come when the end is reached? As John Dewey noted, most people see education as simply "the control of means for achieving ends."[lxxxvii] However, Dewey explained that education is connected to the development of human beings, and as such, it is a process of discovery, and should have "no end beyond itself."[lxxxviii] If education is treated simply as a means to an end then personal development and learning will not happen - education will be reduced to a perverse ritual that tortures the young to conform to competitive social pressures.

Sadly, education in South Korea seems to be a demonstration of Dewey's point: "Education fever" is not about education at all. Schooling is but the means for the relentless pursuit of social status and prestige. Thus, the recently debated phenomenon of "tiger mothers" in the United States should give us pause to think about the means and ends of education.[lxxxix] The education system in South Korea should serve as a warning to the world. It helps us understand how education can be used and abused in the pursuit of social goals, and how children can suffer from their parents' pursuit of an ideal end. South Korea should not be seen as a global educational exemplar. In contrast, the South Korean educational model should serve as a warning. Beware the reduction of education to economic mobility and social status. Beware the grip of "education fever."

Endnotes

[i] Seth, Education Fever, 82-83, 135.

[ii] Ibid., 88.

[iii] Sorensen, “Success and Education in South Korea,” 18.

[iv] Seth, Education Fever, 82-83, 135.

[v] Lee Soo-yeon, "Hagwon Close, but Late-Night Education Goes On," Joong Ang Daily (Aug 17 2009).

[vi] Bae Ji-sook, "Should Hagwon Run Round-the-Clock?" Korea Times (March 13 2008).

[vii] Kim Tae-jong, "Seoul City Council Cancels All-Night Hagwon Plan," Korea Times (March 18 2008); Park Yu-mi and Kim Mi-ju, "Despite Protests, Court Says Hagwon Ban Is Constitutional," Joong Ang Daily (Oct 31 2009).

[viii] John M. Glionna, “South Korean Kids Get a Taste of Boot Camp,” Los Angeles Times.Com (Aug 21 2009).

[ix] James Card, "Life and Death Exams in South Korea," Asia Times Online (Nov 30 2005). Seth, Education Fever, 1.

[x] Casey Lartigue, "You'll Never Guess What South Korea Frowns Upon," Washington Post (May 28 2000); Card, "Life and Death Exams in South Korea;" Seth, Education Fever, 185.

[xi] Koo, “The Changing Faces of Inequality in South Korea,” 12, 14.

[xii] Joseph E. Yi, "Academic Success at Any Cost?" KoreAm: The Korean American Experience (Oct 1 2009); Lartigue, "You'll Never Guess What South Korea Frowns Upon."

[xiii] Moon Gwang-lip, "Statistics Paint Korean Picture," Joong Ang Daily (Dec 15 2009); "Lee Seeks to Cut Educational Costs," Korea Herald (Aug 14 2009).

[xiv] Seth, Education Fever, 172, 187.

[xv] Choe Sang-hun, "Tech Company Helps South Korean Students Ace Entrance Tests," The New York Times (June 1 2009).

[xvi] Seth, Education Fever, 185-86.

[xvii] Hwang Young-jin, "Equity Fund Bets on Cram Schools," Korea Times (n.d.), KEPA papers.

[xviii] KEPA, "The KEPA America Mission," corporate email (Nov 13 2007), KEPA papers.

[xix] Yi, "Academic Success at Any Cost?"

[xx] KEPA, "The KEPA America Mission."

[xxi] Koo, “The Changing Faces of Inequality in South Korea,” 31.

[xxii] KEPA papers.

[xxiii] Kim Tae-jong, "Hagwon Easily Dodge Crackdown," Korea Times (Oct 26 2008); Kang Shin-who, "67 Percent of Private Cram Schools Overcharge Parents," Korea Times (April 14 2009).

[xxiv] "Unforeseen Dangers of Korea's Hagwon Culture," Asian Pacific Post (Jan 10 2006).

[xxv] Ibid., Limb Jae-un, "English Teachers Complain about Certain Hagwon," Joong Ang Daily (Dec 8 2008).

[xxvi] Seth, Education Fever, 192.

[xxvii] Diane Ravitch, The Death and Life of the Great American School System: How Testing and Choice are Undermining Education (New York: Basic, 2010), 107-108, 159.

[xxviii] Darling-Hammond, The Flat World and Education, 70.

[xxix] Ibid., 109.

[xxx] Rose Senior, "Korean Students Silenced by Exams," The Guardian Weekly (Jan 15 2009); Card, "Life and Death Exams in South Korea."

[xxxi] Seth, Education Fever, 170.

[xxxii] Card, "Life and Death Exams in South Korea."

[xxxiii] Hyun-Sung Khang, "Education-Obsessed South Korea," Radio Nederland Wereldomroep (Aug 6 2001).

[xxxiv] Bae Ji-sook, "Should Hagwon Rune Round-the-Clock?;" Soonjae Joo, Chol Shin, Jinkwan Kim, Hyeryeon Yi, Yongkyu Ahn, Minkyu Park, Jehyeong Kim, and Sangduck Lee, “Prevalence and Correlates of Excessive Daytime Sleepiness in High School Students in Korea,” Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 59 (2005): 433-440.

[xxxv] Bae Ji-sook, "Should Hagwon Rune Round-the-Clock?."

[xxxvi] Seth, Education Fever, 168.

[xxxvii] Seth, Education Fever, 166.

[xxxviii] Card, "Life and Death Exams in South Korea."

[xxxix] “Blog commentary by administrative staff in response to CEO interview,” KEPA papers; CEO, “The Road Not Taken,” Corporate email, KEPA papers; S. T., "My KEPA Story," (Dec 12 2007), KEPA papers.

[xl] Promotional handouts and advertising documents, KEPA papers.

[xli] CEO, "From Blended Learning to Critical Learning" (May 15 2009), KEPA Papers.

[xlii] Ibid.

[xliii] Ibid.

[xliv] KEPA, "Critical Learning," ESL Learning Center Business Division (July 2 2009), KEPA papers.

[xlv] CEO, "From Blended Learning to Critical Learning" (May 15 2009), KEPA Papers.

[xlvi] Ibid.; KEPA, "Critical Learning." See also Korean Association for Teachers of English, <www.kate.or.kr/>

[xlvii] Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed (New York: Continuum, 1993), ch 2.

[xlviii] “Interview with KEPA CEO,” KEPA CULTURE MAGAZINE (June 2006), KEPA papers; KEPA, "Critical Learning," ESL Learning Center Business Division (July 2 2009), KEPA papers.

[xlix] CEO, “The Road Not Taken,” Corporate email, KEPA papers.

[l] KEPA, "Critical Learning," ESL Learning Center Business Division (July 2 2009), KEPA papers.

[li] James E. Rosenbaum, Making Inequality: The Hidden Curriculum of High School Tracking (New York: Wiley, 1976); Henry Giroux and David Purpel, Eds., The Hidden Curriculum and Moral Education (Berkeley: McCutchan, 1983).

[lii] CEO, “The Road Not Taken,” Corporate email, KEPA papers.

[liii] Faculty Manager, "Email to Branch Staff," (Jan 7 2010), KEPA papers.

[liv] “Interview with KEPA CEO,” KEPA CULTURE MAGAZINE (June 2006), KEPA papers.

[lv] KEPA, "KEPA Branch(ISE) Head Instructor Guidelines and Expectations," (Aug 18 2009), KEPA papers.

[lvi] C. S., "My KEPA Story," (March 10 2008), KEPA papers.

[lvii] KEPA, "General Trainer's Manual" (Oct 12 2009); KEPA, "Reading and Writing: Track A Program Guide" (Aug 19 2009); KEPA, "CCTV Observation Report" (Feb 2009); KEPA, "KEPA Branch(ISE) Head Instructor Guidelines and Expectations," (Aug 18 2009). All KEPA Papers.

[lviii] “Interview with KEPA CEO,” KEPA CULTURE MAGAZINE (June 2006), KEPA papers; KEPA, "Critical Learning," ESL Learning Center Business Division (July 2 2009), KEPA papers.

[lix] CEO, "From Blended Learning to Critical Learning" (May 15 2009), KEPA Papers.

[lx] KEPA, General Trainer's Manual (Oct 12 2009), KEPA Papers.

[lxi] CEO, “The Road Not Taken,” Corporate email, KEPA papers; Interview with Informant #1 (Nov 1 2009); Interview with Informant #2 (March 6 2010).

[lxii] KEPA, General Trainer's Manual (Oct 12 2009), KEPA Papers.

[lxiii] S. T., "My KEPA Story," (Dec 12 2007), KEPA papers; C. S., "My KEPA Story," (March 10 2008), KEPA papers; C.B., "Success Story," (Nov 14 2007), KEPA papers.

[lxiv] KEPA, KEPA Culture, (May 2009), KEPA papers.

[lxv] KEPA, "Reading and Writing: Track A Program Guide," (Aug 19 2009); KEPA, "Student Counseling Guidelines," (June 25 2009). KEPA papers.

[lxvi] KEPA, "Global Track Overview: Standardized Tests, What Are They and Why Do Students Take Them?" (n.d.); KEPA, "Effective Questioning," Faculty Handout (n.d.); KEPA, "IBT Reading Question Types," Faculty Handout (n.d.); KEPA, "TOFEL iBT Reading," Faculty Handout (n.d.). KEPA papers.

[lxvii] "Student Writing," KEPA papers. On the antagonistic power struggle between students and teachers see Willard Waller, The Sociology of Teaching (New York: Russell & Russell, 1961).

[lxviii] "Student Writing," KEPA papers.

[lxix] Amartya Sen, The Idea of Justice (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009), 124.

[lxx] Ibid., 234-35, 238.

[lxxi] Ibid., 296-97.

[lxxii] UNESCO, South Korea; Hye-Jung Lee, “Higher Education in Korea,” Center for Teaching and Learning, Seoul National University (Feb 2009).

[lxxiii] Moon Gwang-lip, "Statistics Paint Korean Picture," Joong Ang Daily (Dec 15 2009); "Lee Seeks to Cut Educational Costs," Korea Herald (Aug 14 2009).

[lxxiv] Seth, Education Fever, 172, 187.

[lxxv] Seth, Education Fever, 192.

[lxxvi] Rose Senior, "Korean Students Silenced by Exams," The Guardian Weekly (Jan 15 2009); Card, "Life and Death Exams in South Korea."

[lxxvii] Seth, Education Fever, 170; Darling-Hammond, The Flat World and Education, 70.

[lxxviii] Hagen Koo, “The Changing Faces of Inequality in South Korea in the Age of Globalization,” Korean Studies 31 (2007): 1-18.

[lxxix] Koo, “The Changing Faces of Inequality in South Korea in the Age of Globalization”; Andrew Eungi Kim and Innwon Park, “Changing Trends of Work in South Korea: The Rapid Growth of Underemployed and Job Insecurity,” Asian Survey 46, no. 3 (May/June 2006): 437-56; Nelson, Measured Excess; Dennis Lett, In Pursuit of Status: The Making of South Korea’s “New” Urban Middle Class (Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1998).

[lxxx] United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), South Korea, revised version, World Data on Education, 6th ed. (Paris: UNESCO, Oct 2006), 30; Cho Jae-eun, "Too Many Grads Fight for Too Few Jobs," Joong Ang Daily (Oct 18 2010).

[lxxxi] Seth, Education Fever, 100;

[lxxxii] Seth, Education Fever, 102.

[lxxxiii] Lett, In Pursuit of Status, 159, 164; Cho Jae-eun, "Too Many Grads Fight for Too Few Jobs," Joong Ang Daily (Oct 18 2010).

[lxxxiv] Ibid., 212, 215.

[lxxxv] Ibid., 218-19.

[lxxxvi] Pascal, Pensees (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 21. For similar conclusion by a modern academic who studies the "science of happiness" see Daniel Gilbert, Stumbling on Happiness (New York: Vintage, 2007).

[lxxxvii] John Dewey, Democracy and Education (New York: Feather Trail Press, 2009), 28.

[lxxxviii] Ibid., 29.

[lxxxix] Amy Chua, Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother (New York, 2011); Sandra Tsing Loh, "My Chinese American Problem - and Ours," The Atlantic (April 2011) 83-91.